Just as the Coronavirus settled in for its brutal, interminable visit, just as the remnants of life-as-we’ve-always-known-it shattered and collapsed around my ears, a friend nominated me for the Ten Album Challenge. In accepting this challenge, I agreed to post—on Facebook—the covers of ten albums that have influenced or inspired me in some meaningful way.

Right at the beginning, it’s important to note what this isn’t. It’s not a Top-Ten List. These aren’t necessarily my favorite albums of all time. (After all, over time favorites change.) Rather, they are simply ten examples, chosen at random from many dozens, of 12-inch disks that had an influence on my listening habits that might be called lasting.

It’s also worth noting that, in compiling the list, I completely ignored classical music, not because I don’t like it, but to avoid muddying the waters, so to speak. The field of classical music is so vast and deep that it deserves its own lists, and I came to it relatively late in life and with cap in hand for reasons that deserve their own explanation. Another time, another place, perhaps.

So in this list, I concentrate on what I choose to call popular music, with the understanding that the term includes a variety of genres, some of which (modern jazz, anyone?), might not seem as popular as others.

One positive development of throwing such a list together was that the exercise reawakened all my affection for the album format, for the long-playing disk that at the lazy rhythm of 33 1/3 revolutions per minute delivered the miracle of music to a set of ears still malleable and receptive.

One thing I liked about vinyl disks was their size—they were big. When you picked up an album in a record store and hefted it, the thing felt weighty and significant. The album cover had two sides—a front for art, be it photo or painting, and a back for liner notes, which, at least in the field of jazz, developed into its own art form.

But even with rock albums, the notes, when they existed, served a definite purpose. They brought you—the listener—closer to the artist by increasing your knowledge and understanding of him or her or them. In my teens, I became a fanatical reader of liner notes and would spend hours sometimes leafing through the bins in a record store and reading the notes on the back of any album that piqued my interest. And no one, ever, not once in all the years I did this, admonished me; no one ever told me I had to hurry up and buy something or get the hell out.

A quick note on these record stores. At the time (the late 1960s and early 70s), many of them also sold musical instruments. I’m thinking, for example, of the late-and-lamented Spec’s Records in Coral Gables, across South Dixie Highway from the University of Miami, and an easy 10-minute bike ride from our house in South Miami. While working through the bins at Spec’s, I could listen to the staff and certain customers play the guitars and banjoes and mandolins that hung on the walls there. I could also hear them discuss the quality of the instruments, the type of music they esteemed or despised, and even their political views, which were often radical and somehow inextricably tied to the kind of music that preoccupied them.

The point is, this hanging out in record stores was one (free) way to educate myself about the music and musicians I loved. But everything turned around this one artifact, the long-playing 12-inch vinyl disk—an artifact that everyone concerned—the musicians, their fans, the record-store staff and radio disc jockeys—everyone recognized as a form of art. The simple matter of song sequencing on an album was something that musicians and their producers agonized over, if only for the way in which the songs, as they played off against and resonated with each other, would affect the mood of the people who listened to them.

But enough already with the preliminaries. Here’s the list I compiled, on the run and without giving it too much thought, and beginning, as seems reasonable to me, at the very beginning, when, in 1965 and at the age of 13, I started to buy my own albums.

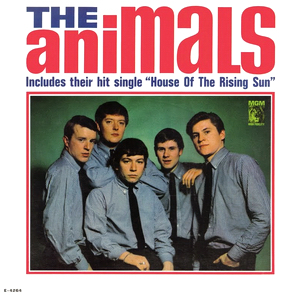

Number One: The Animals. Debut album by one of the major British Invasion groups of the mid-1960s. Two of the five group members were standout musicians: Eric Burdon with his once-in-a-generation voice, and Alan Price, who seemed capable of doing whatever he wanted on piano and electric organ (he used a Vox Continental for “House of the Rising Sun”). Not only did I play this album until the grooves wasted away, but I read the liner notes on the back cover so many times I committed them to memory.

The notes were organized like a table, with one column for each of the five band members. In one section, the member listed his favorite groups and musicians. This came as a revelation to me, because almost none of the listed musicians were rock stars. They were mostly jazz, blues, and R&B musicians, almost all of them were African-American, and the majority of them I’d never listened to myself.

As I played the album tracks (aside from “House”, they were covers of songs by Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, John Lee Hooker, Jimmy Reed, etc.), I had what they call a conversion experience. There was a sense of waking up, and I said to myself, “This changes everything.” I began collecting albums by the musicians who influenced my favorite band, and this probably determined the general tenor of the music I listened to for the rest of my life. They were all there, congregated on the back of this one album: Thelonious Monk, Billie Holiday, Lead Belly, Sarah Vaughan, Charlie Parker, Fats Waller, Dizzy Gillespie, and Bob Dylan, from whose first album, the Animals lifted “House of the Rising Sun” and made it entirely new, completely their own.

The Animals, like many other British groups of the time (Beatles, Rolling Stones, Yardbirds, Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames) adored Ray Charles. Here’s a link to a song from their second album, where they covered one of Ray’s minor masterpieces, something called “I Believe to my Soul:” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NSWJ302wV6k

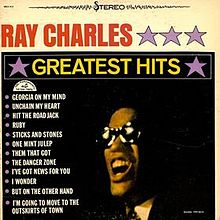

Number 2: Ray Charles: Greatest Hits. Brother Ray released many greatest hits collections over his career, but this was the first, in 1962. It contains a pretty straightforward mix of ballads (“Georgia on My Mind,” “Ruby”) and up tempo R&B (“Hit the Road, Jack,” “Them That Got”). There’s a mean and dirty version of “I’m Gonna Move to the Outskirts of Town,” a song that started life in 1936 as a Country Blues hit by Casey Bill Weldon but that Ray transformed into something more urban, gritty and threatening. How’d he do that? It had a lot to do with soul, which he defined in the following manner for Life magazine in 1966: “Soul is when you take a song and make it part of you—a part that’s so true, so real, people think it must have happened to you… It’s like electricity: we don’t really know what it is, do we? But it’s a force that can light a room. Soul is like electricity, like a spirit, a drive, a power.”

In September 1966, my mother and I went to Dinner Key Auditorium in Miami to see Ray Charles, his big band, and his back-up group the Raelets, which at the time included Merry Clayton, whom the other musicians referred to as “Baby Sister.” This was the same Merry Clayton who, three years later, would deliver such an electrifying duet with Mick Jagger on “Gimme Shelter.”

Some memories of that night. The band performed a warm-up set without Ray. September is a sweltering month in Miami, and the auditorium, a former seaplane hangar, was too big to air condition. After the first couple of songs, the band leader asked the crowd’s permission for the musicians to take off their suit jackets. “Because I can tell you, Ladies and Gentlemen, it is hotter than Hades up here under these lights.” A blistering solo by the 24-year-old guitarist Tony Matthews on the song “Honky Tonk,” a performance so riveting and done with such command that it seemed to take even his fellow band members by surprise. Ray Charles bringing down the house (twice) with his current release, “Let’s Go Get Stoned,” a song I’d been listening to for weeks on WMBM, at the time the only Miami radio station that catered to the Black community.

Here’s a link to the single instrumental on the Greatest Hits album, “One Mint Julep,” where Ray Charles makes the Hammond B-3 snarl and growl like a rabid dog, “like a spirit, a drive, a power:” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gFL0x2ur71E

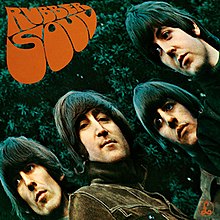

Number 3: The Beatles: Rubber Soul. Anyone who came of listening age in the 1960s was influenced in one way or another by the Beatles. Whoopi Goldberg told Ron Howard that listening to the Beatles inspired her to think, for the first time in her life, that anything was possible, that she could be whatever she wanted to be. She wasn’t speaking just for herself when she said that.

Rubber Soul was always my favorite Beatles album, even after the appearance of Sergeant Pepper’s, The White Album, and Abbey Road. It came into our house shortly after its release through a record club my sister belonged to, and it went back and forth between her record player and mine for many months after that.

It wasn’t uncommon at the time for an album to have a theme or a dominant mood that all its songs reflected in some way. This album’s theme can be summarized in two words: romantic love. This notion—that physical attraction between two people can have an ennobling or spiritual effect on the couple who experience it—was an invention of the French troubadours from the Middle Ages. Rubber Soul serves as an update on this concept by these English troubadours—each of the album’s twelve tracks forms a meditation on a different aspect of romantic love. Just for the hell of it, let’s list those aspects here in no particular order: joy, amazement, confusion, jealousy, desire, affection, contempt, wonder, tenderness, grief, regret, and ecstacy.

Here’s a link to one of John Lennon’s songs on the album. At its finest, his voice had a quality that was simultaneously rough and tender, it created a type of intimacy between him and his listeners that made his best performances unforgettable. “It’s Only Love” is a rather minor piece of poetry that Lennon endows with his own sense of soul, and I mean soul in the Ray Charles sense of the term: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TLvcXs_4QjM

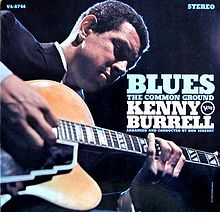

Number 4: Kenny Burrell: Blues, The Common Ground. It’s not just me, Kenny Burrell was also Duke Ellington’s favorite guitarist. Burrell never achieved the fame or commercial success of his contemporaries, Wes Montgomery and George Benson, but among professional guitarists, he was a god, and jazz musicians of all stripes loved to play with him. Maybe his relative lack of fame among the general public was the result of his refusal to court pop success. He remained rooted in the jazz tradition and most especially within the branch of that tradition known as the blues. But his roots went even deeper, reaching all the way down into the gospel hymns he would have heard in the Black churches of Detroit, where he was born and grew up.

Burrell was a skilled and flexible guitarist who could solo either with single-note lines or with a succession of buoyant chords that never lost sight of the melody’s progression. He was also a deft accompanist who knew exactly how to support and enhance the vocalists he worked with. For an example of this that still sounds fresh and revealing, you couldn’t do better than listen to his duets with the cabaret singer Sylvia Syms on the 1965 album Sylvia Is! In particular, check out their renditions of the Broadway standard “As Long as I Live” and Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child.”

One of the things that endears Kenny Burrell to me is that at some point in his prolific career, he started to sneak in one spiritual on each album he released. On the double-disk album Ellington is Forever (a must-have for any serious jazz fan), it was Ellington’s own “Jump for Joy.” On Blues, the Common Ground, he included the traditional hymn “Were You There?” He always played short, one-chorus versions of these spirituals, and he always performed them solo—nuggets of pure gold scattered here and there among his oeuvre. In one of his essays, Emerson defined taste as the recognition of beauty. In this sense of the term, Kenny Burrell had taste to burn.

A related note on “Were You There?” In grad school, I took a course with Father Edmund Colledge, the great scholar and editor of the English mystical writers from the 14th century. He was elderly and verging on frail at the time, but his superiors sent him out every Sunday to say Mass at different parishes on the outskirts of Toronto. In class one day, he started talking about English hymns and then about Negro spirituals, and then he mentioned “Were You There?” “You know,” he said, “I do wish they wouldn’t sing that damn song when I’m distributing communion, because every time I hear it, I’m afraid I’ll break down and cry.” Here it is, Kenny Burrell and “Were You There?”—sometimes it causes me to tremble: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qvH_07EI5lM

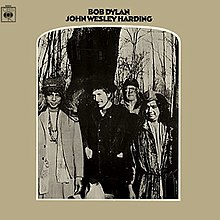

Number 5: Bob Dylan: John Wesley Harding. Sometime early in 1968, when I was 15, I was lying in bed with the lights off and listening to the Miami station WBUS-FM on a transistor radio. They were playing a talking blues with a simple acoustic accompaniment of guitar, bass, and drums. The singer sounded vaguely familiar, but the subject matter was unlike anything I’d ever heard. At the end, the deejay identified the song as “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest,” from Bob Dylan’s new album, John Wesley Harding. I went down to Spec’s Records the next day and bought the album, then came home and listened to it three or four times in a row. The same feeling as from the night before settled over me—a mixture of strangeness and familiarity that grew into a sense of what I can only describe as wonder.

This was the first album Dylan released after the motorcycle accident that nearly killed him. The brush with death may have pushed him to redefine his music. Gone were the clanging guitars and seething organ of Highway 61 and Blonde on Blonde. He replaced them with an acoustic presence so understated that at times it seemed he was singing a cappella. Gone too was the preoccupation with romantic entanglements and social protest. Instead, the theme of the album—or at least of the first ten of its twelve tracks—could be summed up in a single word: sin.

This focus on sin, on the evil that people do and the way that evil corrupts them and the society in which they live, is confirmed by the biblical references that Dylan sprinkled throughout those first ten songs. The imagery of the album’s most famous song, “All along the Watchtower,” comes directly from the Book of Isaiah, and “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” has nothing to do with the historical Bishop of Hippo, but serves as a composite portrait of an Old Testament prophet, one who was scorned, derided, and finally killed by the people he was sent to save.

So maybe Dylan’s greatest achievement with John Wesley Harding was that he radically expanded the subject matter of rock or folk-rock or whatever you want to call the music he played. Written in the valley of the shadow of death, this album confirmed that popular music was capable of treating the most profound questions that confront men and women during their winding passage from cradle to the grave. Here’s a link to a song that seems even more timely today that when it was released, that perfectly succinct expression of fear and confusion, of the sense that death might be a lot closer than we’d like to think, “All along the Watchtower:” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bT7Hj-ea0VE

Brilliant, Ed.

Brought back some memories of my own: the furniture store on Western Avenue in Chicago where I sourced my vinyl. Seeing/hearing Ray Charles at the Ontario Place Forum on July 4, 1976, the U.S. Bicentennial. I thought, how nice for him to give up his US holiday to spend it with us in Canada.

Love your Fr. Colledge story.

And hats off to all of the transistor radio stations of our youths — WCFL and WLS in Chicago, for the Silver Dollar Survey of hits, that would see, Sinatra, Elvis, the Beatles, and Dusty Springfield on the same list on any given week. Also WOPA, for the psychedelic hippie music, and WVON (“Voice of Negro”) for soul and blues.

And the Animals’ “We Gotta Get Out of this Place” became my secret high school theme song, until I got out of that place.

Best to you.

Thanks, Vid–very glad you enjoyed it. It’s amazing the memories that come flooding back once you start thinking of the music you listened to in your youth.