Here is the second instalment of the list I drew up in May for the so-called Ten Album Challenge. In revising the text for these last five albums, I discovered a rather pressing urge to say something more about Billie Holiday and Captain Beefheart in particular. The first because her far-reaching shadow seemed to touch, almost to the point of obscuring, every other artist on the list; and the second simply because I find his music, and the personality that animated it, to be endlessly fascinating.

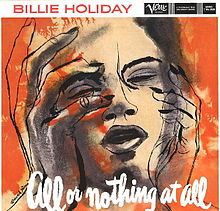

Number Six: Billie Holiday: All or Nothing at All. In his meditative long poem Four Quartets, T.S. Eliot said: “The communication of the dead is tongued with a fire beyond the language of the living.” This album came out in 1959, the same year Holiday died at the age of 44, handcuffed to a hospital bed in New York City. The disk was recorded in Hollywood two years earlier, and one of the things that lends it fire is the quality of her sidemen—Holiday always attracted gifted musicians and seemed to bring out the best in them. When she was young, it was people like Teddy Wilson on piano and Lester Young on tenor sax. She toured with the Count Basie Band in one of its finest early incarnations and later with Artie Shaw’s legendary big band. While she was honing her musical skills on these tours across the United States, she also learned how to deal with discrimination and bigotry on a daily basis. “You had to smile,” she said once, “to keep from throwing up.”

On this album, Holiday had the support of another great sax player, her one-time lover, Ben Webster; and of Jimmy Rowles, a disciple of Wilson’s, on piano; the Basie alumnus and trumpeter Harry “Sweets” Edison; and Barney Kessel on guitar. The music has a relaxed, flowing style that’s almost sprightly at times and seems to reflect the affection that existed between the vocalist and her men. Maybe Rowles spoke for them all when, twelve years after Billie’s death, he told an interviewer, “Too much chick—oh, how I loved her.”

Then there’s that voice, a voice so distinctive, so instantly recognizable, that it put an indelible stamp on every song she sang. Of course, anything so idiosyncratic would not be to everyone’s taste. For one, Ethel Waters, another renowned stylist, complained that Holiday sang like “her shoes were too tight.” And many critics find that Billie’s later recordings, made when she was in the grip of twin addictions to alcohol and smack, suffer in comparison with the disks she cut in the 1930s.

I can’t say I agree with that assessment, at least not in regard to this album. Her vocal phrasing, which she modeled after the horn players she admired, seems spot on, and in the faster numbers particularly she sings with an energy and conviction that really swings. For me, her greatest asset as a vocalist was always that she knew how to tell a story, and this was a skill that the hellish aspects of her later years only seemed to amplify. The authors of The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings believed that this album contains “what is probably Holiday’s most regal, instinctual late work.”

I’ve often asked myself what gave Holiday’s voice its personality, its ability to hook her listeners immediately and then to keep them enthralled. It’s possible that a few sentences from her autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, hold a key to unlocking at least part of this mystery. “When I was thirteen, I got real evil one time and set on my ways. I just plain decided one day I wasn’t going to do anything or say anything unless I meant it. Not ‘Please, sir.’ Not ‘Thank you, ma’am.’ Nothing. Unless I meant it.”

I suppose this is the quality I recognize in her singing and that makes her voice so attractive: an uncompromising demand for authenticity. And that one word—“nothing” followed by a period—rings through her life and through the recordings she left us with the same force, the same tragic consequences, as when it fell from Cordelia’s lips in the opening scene of King Lear. Holiday’s life—in her rise to greatness against the brutal odds of poverty and racism, in her tragic fall into addiction and an early death—had an arc and a glow and a darkness at the end that can only be described as Shakespearean.

As for this album, if we must have favorites, mine are the two Gershwin songs, that pair of ineffable showtunes, “But Not for Me,” and “Our Love Is Here to Stay.”

Number 7: Dave Holland Quartet: Conference of the Birds. Whenever someone says to me, “I can’t stand modern jazz,” I respond in one of two ways. One, I shrug my shoulders and let it go at that. After all, people are entitled to their likes and dislikes. Two, if I sense even an inkling of hope, I say, “Have you ever listened to Conference of the Birds?” Over the years, the title song from this album has often proved to be the thin edge of the wedge, the incisive tool that’s pried open many an ear to the beauty of this type of music.

Dave Holland is a British bassist who, at the age of 22, started working with Miles Davis on some of his later albums, including Filles de Kilimanjaro and Bitches Brew. For this album, Holland put together a quartet that included the prodigiously gifted Anthony Braxton on saxophones and flute, Sam Rivers, also on sax and flute, and Barry Altschul on drums and marimba. All of these musicians would go on to have distinguished careers in avant-garde jazz.

As I said in the introduction to these ten albums, I’ve always been a great reader of the liner notes on album covers, but especially on jazz albums, where these notes have achieved the status of a minor art form. Think of Leonard Feather, Nat Hentoff, and Michael Cuscuna, among many others. Think of the essay Bill Evans wrote for Kind of Blue, where he compared jazz improvisation to Japanese ink painting.

The notes on Conference of the Birds were written by Holland himself. In their restraint, brevity, and directness, they form a perfect reflection of the music the album contains: “While living in London I had an apartment with a small garden. During the summer around 4 or 5 o’clock in the morning, just as the day began, birds would gather here one by one and sing together, each declaring its freedom in song. It is my wish to share this same spirit with other musicians, and communicate it to the people.”

Each song on the album follows the same basic pattern: a statement of the theme, free improvisation, then a re-statement of the theme at the end. Now that summer’s here in North America, this seems a fine time to acquaint ourselves with this particular declaration of freedom in song. Here it is, the Dave Holland Quartet and “Conference of the Birds.” Open your ears—you won’t regret it.

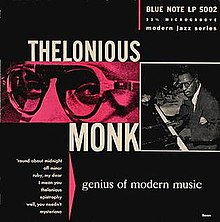

Number 8: Thelonious Monk: Genius of Modern Music. When he was a young man and still living at his mother’s place in the San Juan Hill district of New York City, Monk taped a photograph of Billie Holiday to his bedroom ceiling so that her face would be the first thing he saw when he opened his eyes each morning. In some ways, Monk was the instrumental equivalent of Billie’s voice. His compositions—more than 60 of which remain in the standard repertoire—are so distinctive in style and tone that they’re instantly recognizable as his—no one else wrote that way, and no other pianist played like him. Ethan Iverson, writing in the New Yorker on the 100th anniversary of Monk’s birth, described his music as a perfect package of “accessible surrealism.”

Monk was something of a Janus figure: he looked back and ahead simultaneously. One reason his music seemed so original on a first hearing was that he’d completely absorbed the technical innovations of the musicians who preceded him. Goethe said: “The rules are but a springboard and we’re free.” If we substitute “past” for “rules,” we can begin to understand the basis of Monk’s sometimes disquieting originality.

I bought my first Monk album, egged on by my favorite band, The Animals, when I was 14. Aside from Bob Dylan, no single musician has provided me with more pleasure over the course of my listening life than Monk. I’ve also used his albums as a kind of road map to discover other jazz musicians and to explore the history of the art form. He played with the best—John Coltrane, Coleman Hawkins, Milt Jackson, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Art Blakey—the list goes on and on. Coltrane adored Monk, partly because he was such a patient and generous teacher, and partly because, as a band leader, he was so demanding and full of surprises. “I always had to be alert with Monk,” he told one interviewer. “Because if you didn’t keep aware all the time of what was going on, you’d suddenly feel as if you’d stepped into an empty elevator shaft.”

The songs on this album were recorded in 1947—early in Monk’s career—and released by Blue Note on vinyl in 1951 and on CD in 1989. They still sound fresh and exciting. Some people complain about Monk’s so-called percussive style of piano playing, but I’ve always loved his insistently oblique approach. Even though he played so well with horns, I’ve chosen to feature one of the songs he did in trio format—“Well, You Needn’t”—because it shows how hard he could swing when he wanted to.

Number 9: Sarah Vaughan: Sarah Vaughan. I came to Sarah Vaughan relatively late in life and through a side door, so to speak. I’d seen a clip of the trumpeter Clifford Brown on TV and was so impressed I started collecting his albums. There weren’t that many, since he died in a car accident at the age of 25. In 1954, two years before his death, he served as a sideman on this album, one of the few that Vaughan recorded with a small group. Like Billie Holiday, she spent a significant part of her early career touring with big bands, in her case those of Earl Hines and Billy Eckstine, and she retained a preference for the big-band format to the end of her career.

Her voice wasn’t as superficially distinctive—it didn’t carry an instantly recognizable signature—as those of Billie Holiday or Ella Fitzgerald. (She had a somewhat morbid sense of humor, and once she became famous, she’d tell her concert audience that her name was really Della Reese or Carmen McRae.) What distinguished her voice from those of the competition was perfect pitch in the most profound sense of the term. Vaughan didn’t just nail the notes; she seemed to drill into the middle of each syllable she sang and inflate it from within.

She was murder on ballads and took them at the slowest of tempos, not just to emphasize the sadness at the heart of the song, but to show what she could do with the lyrics. Here, on “April in Paris,” the second time she sings the line “Never missed a warm embrace,” she drops her voice on the word “warm” and stretches it out to two syllables, as if breathing on a coal to bring it back to life.

I thought I had a pretty comprehensive knowledge—through Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett and others—of the American songbook, but this album inspired me to examine it all over again, and as if hearing it for the first time, through the medium of Sarah Vaughan’s incandescent voice. Late in her career, she developed what the critic Whitney Balliett called her “candelabra approach,” in which a rococo vocal technique sometimes hogged the spotlight. But on this album she was at her best, perhaps because she was still discovering what that best could be. Here’s a link to “April in Paris,” which also includes three stunning solos from her sidemen.

Number 10: Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band: Clear Spot. If you’ve been following along from the start of this posting, you’ll realize by now that many of the musicians I’ve chosen to feature are distinguished by a common trait, that of individuality. In other words, their music expresses something of their personality, of that mysterious quality that sets them apart from everyone else and gives them a unique point of view. In this sense it’s fitting to end with Captain Beefheart, a.k.a. Don Van Vliet, that non pareil of the sui generis and one of the great iconoclasts of rock. The only other ’60s musician who resembled him was his high-school chum and sometime producer Frank Zappa; together they formed a school of two. While Zappa achieved a certain fame during his career (and after his death), Captain Beefheart, in spite of the following he developed among the rock-and-roll cognoscenti, remained in obscurity until he retired from the scene in the 1980s to devote himself fulltime to painting.

I started hearing about Captain Beefheart in the early 1970s at the University of Toronto. Clear Spot was the album people recommended, partly because it had just been released, and partly because it was one of the Captain’s more approachable records. Trout Mask Replica, Beefheart’s magnum opus, was more like graduate school. You had to train, to prepare yourself before approaching that unclassifiable masterpiece. Even the best critics have had trouble describing it in a way that can encapsulate its contradictory charms. Here’s a sample from Peter Keepnews, writing in Downbeat in 1981: “Trout Mask is a sprawling, frightening, at times hilarious, at times heartbreaking, at times impossibly self-indulgent work…. the ravings of a man between genius and insanity.” Or, as Van Vliet explained to this same critic, “I just think my music doesn’t fit on the conveyor belt.”

As with many geniuses, Don Van Vliet could be difficult, both as a person and a musician. The guitarist Ry Cooder left the Magic Band in 1967, incensed at the high-handed way Van Vliet treated the other musicians. “He’s a Nazi,” said Cooder. “It makes you feel like Anne Frank to be around him.” The only time I saw Captain Beefheart perform—in 1974 at the University of Toronto’s Convocation Hall—he walked off stage after two numbers because he didn’t like the building’s vibe. Can’t say I blame him.

Because of its experimental nature, Captain Beefheart’s music does seem opaque at times. For some of the songs on Trout Mask Replica, each member of the Magic Band would play in a different key or time signature. In spite of these attempts to obliterate harmony or the concept of time itself, many of Beefheart’s songs are enticing even on a first hearing. This is often because his music is so steeped in the blues. Certain influences are apparent. Howlin’ Wolf, Ray Charles, and Dr. John are present in his vocal phrasing. His harmonica work carries traces of Junior Wells and Bob Dylan. And you can hear something of Thelonious Monk and Ornette Coleman in his unexpected harmonies and the abrupt detours of his melodies. Van Vliet himself denied, to a succession of interviewers, that he had any influences at all. “I was never influenced,” he told one. “Possessed, but never influenced.”

I’m a sucker for a good ballad, and Captain Beefheart, perhaps surprisingly, was a fine composer of slow-tempo love songs. Here’s a link to “My Head Is My Only House Unless It Rains,” as good a place as any to start if you’re listening to him for the first time.

Wow, Ed. This was quite a journey. I sat down this morning with a cup of tea and listened to each one.

I took a few notes, which I might just paste below. Thanks for a great journey!

Billie Holiday: All or Nothing at All.

Always loved her voice. But I loved the back story even more. It made me listen harder. True this: “an uncompromising demand for authenticity.”

Thelonious Monk – Well, You Needn’t (1947)

That piano!!! The first time I heard of him was from “Maynard G. Krebbs” on the Dobie Gillis show in the early 1960s. 🙂 He loved Thelonious Monk, which, of course still sticks with me some 60 years later. I never really listened until today. So glad I did.

Sarah Vaughn

I have always loved her voice, too. But this one, in particular, may have lowered my blood pressure. Talk about settling back and letting yourself get into the moment. Thanks for this heads-up: “Here, on ‘April in Paris,’ the second time she sings the line ‘Never missed a warm embrace,’ she drops her voice on the word ‘warm’ and stretches it out to two syllables, as if breathing on a coal to bring it back to life.”

I listened for it, and there it was, as “warned.”

Conference of the Birds

This one was interesting. I might not have appreciated it as much if I hadn’t read the story behind it. It does conjure up the birds celebrating their freedom in sound. My husband and I remarked about that very sound this early morning while walking our dog. It is another world, one we often miss these days.

(Aside: Last winter, we attended a SC Philharmonic Orchestra presentation, during which they played a “Re-imaged Vivaldi” version by Max Richter. Vivaldi has been done to death, so we weren’t sure what we were in for. But this version – especially when watching every instrument playing the notes with such passion – was almost hypnotic. A swarm of arms moving in tandem on stage, at breakneck speed, to keep the sounds of spring coming alive. Anyway…it “kind of” reminded me of Conference of the Birds – just another medium.

https://youtu.be/8oYWfJuMGMA

Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band: Clear Spot.

“My Head is My Only House Unless it Rains

I like the easy rhythm of the song you chose for this one. And this line: “My arms are just two things in the way til I wrap them around you.” What a personal look into someone’s soul.

I think I can understand this…lol…“He’s a Nazi,” said Cooder. “It makes you feel like Anne Frank to be around him.”

Often it seems to come with the territory of off-the-chart talent.

What a great way to start a Saturday morning. Really enjoyed it.

Many thanks, Mary Ann–you’re something like my dream reader. You actually read, and listen, and think about what’s been said and then respond. Quite often with these posts, it’s like dropping a coin down a well–you can’t even hear the splash at the end. I’m glad you enjoyed the post and the musicians whom I chose to profile. Even though their music speaks for itself, I find it fascinating to learn about their lives and the way they responded to their own peculiar challenges. And one interesting thing I realized while putting together this list of ten albums was that it would be quite easy to draw up another list of ten “also-rans.” Maybe I’ll get around to that one of these days.

Ha! I love that metaphor about the well. Perfect. I often look back at my teaching years and wonder if all that work with those goofy middle school students make up the “silent splashes” in my own well.

Your efforts deserve to be read and listened to. There’s a lot of heart in your work, and that’s worth listening to. Plus, thanks to my relatively new “writing gig,” I’m always looking to learn from other writers’ sentences (and metaphors), and your writing is so lovely.

I like learning about things I haven’t thought about in a while. After living in South Jersey for 18 years, attending college at Fairleigh Dickinson U. (“Fairly Ridiculous” was its local nickname) was a step into another world. Just fifteen minutes from NYC via bus (which is one of the reasons I picked the school), I graduated from 13 years of small-town, Catholic school, culture to a veritable banquet of new learning experiences. Many of the people with whom I attended college were from New York and knew all the cool Village places to go to. (East and West back then, depending on our current appetite. Beaded doorways, patchouli scents (!) drifting from each shop, late night strolls…wow. We saw people like John Lennon, walking silently down the street across from us one late night as we walked to the bus station. No one even screamed or ran after him. 🙂 I heard so many different kinds of music to which I was never exposed in our little town of Woodbury. And because we were so close to NYC, we got to see a lot of famous people at our little school (Laura Nyro was one), James Taylor and Carol King, in their early days came to our cafeteria and played and sang and interacted with our small group. I arrived in 1969 after the summer of Woodstock, so a lot of people I knew had been there. I had heard of Joe Walsh, for example, but never heard a full album by “The James Gang.” I was introduced to so much rich music, and boy were those the days of cool music!

Anyway, sorry to go on like that. It’s just great to indulge in a really good writer’s interest in different kinds of music – and to keep on learning.

Thank you so much for the opportunity to do so!!

Mary Ann 🙂