I spent a year at the University of Toronto reading the epic poem Beowulf in the original Anglo-Saxon. The prof for that class was Laurence K. Shook, a Basilian priest who had a special interest in the riddles contained in an Old English manuscript called the Exeter Book. These riddles all take the form of short poems in alliterative verse, and none of them comes with a solution. Shook believed several of the riddles referred to birds that were common in England during Anglo-Saxon times.

One evening when Father Shook was talking about the riddles, one of my classmates snickered. The priest had just made a passing remark to the effect that birds like people. When he heard that snort of laughter, which was both derisive and dismissive, Shook paused then leaned forward and patted the table we all sat around with both hands. “Oh, it’s true,” he exclaimed. “Birds (pat) like (pat) people (pat, pat).”

The memory of this moment surfaced many years later, around the time I became what is known as a serious birder. As years passed, and I learned more about the creatures that fascinated me, I came to agree with Shook. For any number of reasons, it seems undeniable that birds really do like people, the only riddle being why they appear to like certain people more than others. But given that that’s the case, the other thing I’ve noticed is this: that the way birds reward the people they like is by revealing themselves to them.

~

In the letter he wrote to his wife about the Fair Incognito, Audubon said that when she dismissed him on that first day, he was so eager to leave that he “felt like a Bird that makes his escape from a strong Cage, filled with sweet Meats.” Once sprung, he walked the streets for an hour, trying to prepare himself for the sight of her naked body, for the unabashed display of what he referred to as “her sacred beauties.”

On his return, he finds her waiting impatiently in the same upstairs room. She notices at once that he’s still trembling slightly. “What a man you are,” she says. Then, partly to forestall any hesitancy on his end, partly because she enjoys the sense of control she exerts over him, she pushes him toward what they both know will be the decisive moment.

First she hands him a box of fine chalks, then she pulls a large sheet of paper from the drawer of an armoire. The paper is of a size known as “elephant folio,” which is the same sized sheet Audubon used to draw his life-sized birds. With a piece of chalk in his hand and the familiar paper before him, he grows calmer. The woman disappears from view as she draws the curtains around a “superbly decorated” couch. He hears the rustle of clothing as she undresses. A moment of silence, then she bids him open the curtains. He sweeps them aside and feasts his eyes on her unblemished flesh. “I drew the curtain,” he wrote to his wife, “and saw this Beauty.”

“Will I do so?” she asks. Stretched full length on the couch, like Goya’s Naked Maja, her body glows in the afternoon light that falls through the room’s long windows. It occurs to Audubon that she has arranged and rehearsed everything beforehand, down to the finest detail, to make the strongest possible impression on the eye of the artist. He’s so entranced by the sight of her nakedness that he drops his piece of chalk, a sign not just of nervousness but of the sexual desire that threatens to overwhelm him. He confessed as much to his wife: “Shut up with a beautiful young woman as much a Stranger to me as I was to her, I could not well reconcile all the feelings that were necessary to draw well, without mingling with them some of a very different nature.”

He retrieves his chalk and sets to work. After nearly an hour, his subject begins to feel “a little Chill” and asks him to draw the curtains so she can dress herself again. Once clothed, it is her turn to feel an excitement she can barely contain. “Is it like me?” she says of Audubon’s sketch, then repeats herself with a childlike eagerness. “Will it be like me? I hope it will be a likeness.”

She inspects what he’s done and immediately detects a minor flaw, perhaps, as the biographer Richard Rhodes suggested, a fault in foreshortening, a technique that Audubon hadn’t fully mastered at this point in his career. She points out the mistake and makes him correct it, and this marks her first contribution to what will become a collaboration between the still developing artist and his equally gifted model.

“I wish it was done,” she declares and then makes a strange admission. She realizes that wanting to have a drawing of herself in the nude is “a Folly,” but the truth is, “all our Sex is more or Less So.”

She pulls a bell rope, and a maid wheels in a dolly loaded with cakes and wine. Audubon refreshes himself, then works for another two hours to complete his sketch, while the woman peppers him with questions about his family, his drawings, and his way of life. Even while he concentrates on finishing the sketch, Audubon feels his admiration for this “well informed femelle” begin to expand beyond his first focus on her physical beauty. In her conversation, he says, she always uses “the best expressions,” and she possesses “the manners necessary to Insure Respect and wonder.”

~

This first day serves as a template for the routine the two of them will follow over the next nine. The woman lies naked on the couch for an hour while Audubon draws from life. Then she dresses herself and converses with him while he works on various details for another two hours. When Audubon leaves for the day, the drawing stays behind, and when he arrives the following day, he always finds that she has made improvements to his work over night. Audubon was rarely generous in his assessments of fellow-artists, whom he considered rivals for public esteem and financial rewards, but he admitted to his wife that the Fair Incognito had the ability to work “in a style much superior to mine.”

In the end, the woman’s contributions to the drawing are so extensive that it might be called a self-portrait. “I finished my Drawing,” Audubon told his wife, “or rather she did for when I returned every day I always found the work much advanced, she touched it she said … because She felt happy mingling her talents with mine.” On the last day, the woman shows him the frame she has bought for the drawing, and once Audubon has framed the portrait, she signs it for both of them, but in a way that makes their respective contributions clear: “She put her name at the foot of the drawing as if her own and mine in a dark Shadded part of Drapery.”

~

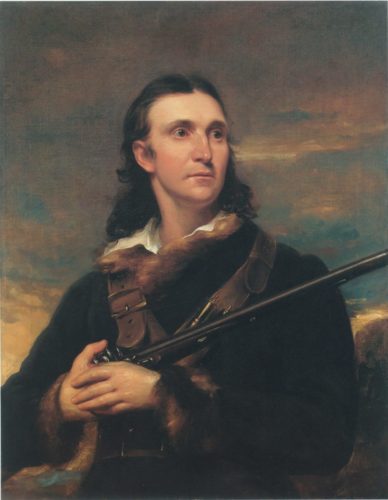

Much of the rest of Audubon’s letter deals with the payment he received for this portrait. In spite of his poverty and obvious need, the payment did not consist of cash but took the form of a gift, what the woman called un souvenir or keepsake. She decided what this keepsake would be, and her choice, strange as it might seem, served to define the nature of her relationship with the artist. Without any prompting from Audubon, she decided to give him a gun.

“One who hunts so much,” she said, “needs a good Gun or Two[.] [T]his afternoon see if there is one in the City & give this on a/c if you wish to please me to the last.” She hands him a five-dollar bill, which Audubon uses to make a down payment on a double-barreled shotgun he finds selling for $120. She insists on seeing the gun before giving him the rest of the money, and then on having one of the barrels inscribed with a dedication in French: Ne refuse pas ce don d’une amie qui t’est reconnaissante[.] [P]uisse t’il t’égaler en bonté. [Don’t refuse this gift from a friend who is grateful to you. May it equal you in goodness.]

When she says goodbye on the last day, she gives him “a delightful Kiss” and says, “Be happy [and] think of me sometimes as you rest on your gun.” Freud would have had a field day, but for us the question remains, Why a gun? Why did she choose to give him a weapon rather than money or any other item he might have put to use—a suit of clothes, for instance, a ream of drawing paper, or a few cases of fine wine?

The answer lies in the type of relationship that these two people worked out between themselves, which was a relationship not so much between a woman and a man as between a bird and the artist who kills it first then brings it back to life on paper. It’s tempting to say that by giving him the gun, the Fair Incognito put her own stamp of approval on the way Audubon preferred to think of her: not so much as a woman who tempted him with her charms, but as a bird that challenged him to capture it on paper.

After all, Audubon, in his relations with the birds he drew, always had two instruments at hand: a gun to kill and a piece of chalk to draw. By the end of their 10-day relationship, the woman has made him a gift of both these instruments: the chalk on the first day and the gun on the last. That their usual order of appearance (gun first, then chalk) is reversed doesn’t make their presence any less significant.

Then there is the word, “femelle,” that Audubon used three times in the letter to his wife to describe the Fair Incognito (a femelle of a fine form … a well informed femelle … this extraordinary femelle). In French, femelle is primarily a zoological term used to denote the female of a species other than human, and it was a term Audubon often used in discussing birds.

But if I say merely that Audubon tried to sublimate his sexual longing for the Fair Incognito by reducing her to the level of a bird, does that really get at the heart of his relationship with her? Or was that relationship—and her role within it—something darker and more complex? To understand the real threat that the Fair Incognito posed for him, it would help to outline in point form the standard stages in Audubon’s dealings with the birds he drew.

Those stages consisted of the following five:

– The hunt: first Audubon had to find the bird, which could involve pursuing it for days or weeks at a time.

– The shot: Once he found the bird, Audubon killed it to bring it close and hold it still while he studied the details of structure and plumage.

– The posing: Audubon developed his own form of taxidermy. He passed wires through the bird’s body parts to arrange it in a lifelike pose, then fixed it to a wooden board divided into equal squares, which helped with matters of perspective and proportion.

– The drawing. Audubon used different colored chalks to draw the bird life-sized on a large sheet of paper known as elephant folio.

– Publication: For all the birds Audubon drew, this involved two parts: as a print in The Birds of America, and as a written description in a companion volume called the Ornithological Biography.

If we examine these same five stages as they apply to Audubon’s relationship with the Fair Incognito, what we see immediately is not so much that he thought of her as a bird, but that she treated him as one. Suddenly, the odd image that Audubon used to describe his feelings on leaving her house that first day—of a bird escaping from a cage—makes sense. We understand that the real threat she posed was not as a seductress but as an identity thief. By robbing Audubon of his own identity and assuming it herself, she succeeded in reducing the active hunter and creative artist to the role of a passive bystander.

Only consider:

– The hunt: In the letter to his wife, Audubon noted that the woman employed one of her servants to watch and follow him for days: “for several nights this servant had remained very late to see if I absented from the Boat [where he was living] and that in fact She knew every Step I had taken since the day She had resolved on employing me.” Once she’s familiar with his habits and routines, she accosts him in person on the Rue Royale.

– The shot: As noted above, when she pronounces the word naked, Audubon feels as if he’s taken a cannonball to the chest: “had I been shot with a 48 pounder through the Heart my articulating powers could not have been more suddenly stopped…. I felt such a blush and such Deathness through me I could not answer.” From this point on, he does whatever she asks and never once asserts himself.

– The posing: Audubon doesn’t tell the woman how to lie on her “superbly decorated” couch; rather, she arranges herself, and Audubon says only: “I Eyed her but dropd my black Lead pencil … perceiving at once that the Position, the light and all had been carefully Studied before.” Once again, she plays the active role, and he the passive, and by removing her clothes and lying still on the couch, she transforms herself into something wild, something he will struggle to capture.

– The drawing: Audubon uses the same materials—chalk and an outsized piece of paper—to draw the Fair Incognito that he uses with his birds. But every night after he leaves, she takes possession of these same materials to improve the work he has done. By doing so, she assumes the role of the master craftsman who corrects the work of her apprentice. When the portrait is finished, she signs it herself and puts his name off to the side.

– Publication: Instead of publishing the portrait for others to see, the Fair Incognito hides it from public view and disappears from Audubon’s life forever. “She never askd me to go see her when we parted, and I have tried several times in vain, the Servants always saying Madame is absent.” However, just as he did for all his birds, Audubon sets down a second, written, portrait of “this extraordinary femelle” in the letter to his wife. It’s as if he needed to put his relationship with her into words, not just to understand what happened, but to assure himself that he survived the experience with his faculties intact.

Outlining these five steps helps us to appreciate what a radical role reversal the Fair Incognito engineered in her dealings with Audubon. We can see that the most surprising aspect of their relationship was not her willingness to expose her “sacred beauties” to the gaze of a stranger, but the intelligent and determined way in which she controlled the process of producing her portrait. Not only does she use all the instruments and materials Audubon used in drawing his birds, but she also assumes all the roles. She is both model and artist, hunter and prey, the one who kills and the one who resurrects. In her active agency, she goes so far as to steal Audubon’s identity from him until at the end she returns it by giving him the gun.

With gun in hand, Audubon is no longer the passive and cowed collaborator he became from the moment she tracked him down on the Rue Royale and challenged him to draw her nude. Now he’s the hunter again, and he’s free once more to resume his role as the master craftsman, the artist.

And what of the Fair Incognito? Because the gun she gives to Audubon also means something to her. In fact, it represents a form of suicide, since immediately after paying for it, she disappears from his life forever. It’s worth observing that in French—the language these two eccentric souls used to communicate with each other—the word disparaître means both to vanish and to die. Once the woman has finished her portrait, she’s free, free to disappear and take her “likeness” with her, but also free to restore Audubon’s identity to him. She does this by giving him the gun, a symbol of his role as hunter and artist, and a reminder of something they both knew instinctively: that every truly creative act takes place in the shadow of death.

This is great, Ed! Really enjoyed it.

Thanks, Bob–it’s good to know that you enjoyed the piece–even though it took a while, I had a blast writing it.