When she stops him on the Rue Royale, she’s wearing a dark veil that makes it impossible to see her face. Even so, he can tell she is “a femelle of a fine form.” She speaks to him in French because she knows it’s his native tongue. Is he the man who draws the birds in black chalk? In fact, she knows quite a bit about him—she’s had him followed for days—and he knows nothing of her.

Yes, he admits to working in that medium. Well in that case, she says, come to such-and-such an address in thirty minutes. Then she climbs into a waiting carriage and disappears. He walks to a nearby bookstore, where he struggles to compose himself. Even in New Orleans, it’s unheard of for a respectable woman to speak to a strange man on the street. He’s overwhelmed by what he calls “a feeling of astonishment undescribable.”

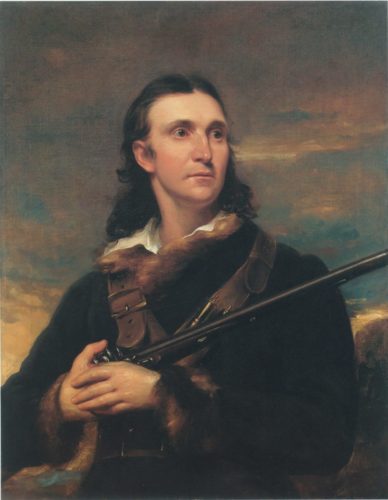

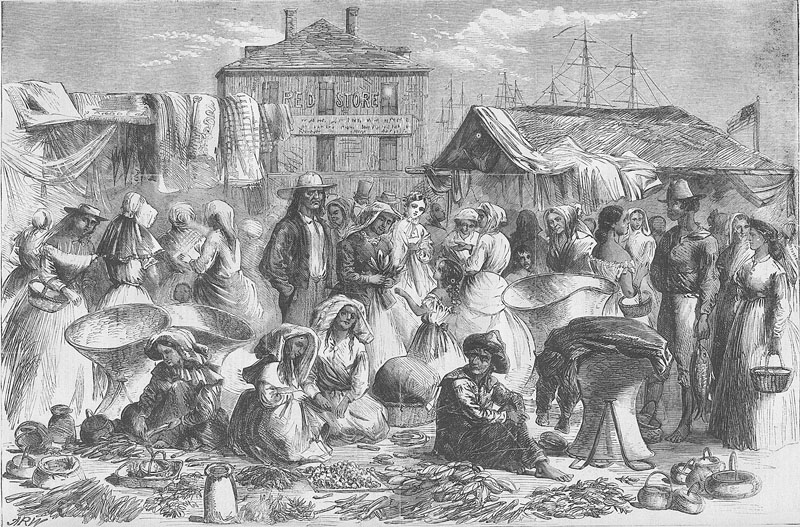

This is 1821. John James Audubon is thirty-five years old. He arrived in New Orleans (his second visit to that still “frenchified” city) two months earlier, broke and bedraggled after coming down the Mississippi and Ohio rivers on a flatboat from Cincinnati, where he’d left his wife and children. He’d spent his time on the river shooting birds for the communal pot and drawing those that intrigued him.

When the young woman, whom he would come to call the Fair Incognito, stops him, he’s carrying a wooden portfolio case that contains his most recent drawings. The case is large and lined with tin to keep out the rats that ruined several earlier works. He’s lugged this unwieldy box all over the city trying to drum up portrait commissions and other employment. Almost every cent he’s earned—more than $200.00—has gone back to his wife in Cincinnati. He’s been so busy drawing portraits and promoting himself that he hasn’t found time to buy new clothes or visit the barber. Audubon’s hair hangs down to his shoulders, his face is still sunburnt from the river journey, and he’s dressed, essentially, in rags.

His appearance speaks so eloquently of need that some of his old acquaintances have stopped speaking to him on the street. But now, “this extraordinary femelle” has sought him out and invited him home. What awaits him there?

∞

The address she’s given him is in a new development, a suburb of New Orleans called the Faubourg Marigny. She lives, appropriately, on a street called Rue d’Amour. When he arrives at the appointed time, a servant shows him upstairs and into a room where the woman, still veiled, is waiting. Once they are alone, she rises from her chair, shuts the door, and secures it with a double lock. Only then does she lift the veil to show him her face, which he judges to be “one of the most beautifull” he has ever seen.

The excitement he feels is so intense it frightens him. She asks if he is married and then notices he’s trembling. She offers him a drink. Audubon, curiously for a Frenchman of his time, has never been much of a boozer, but he downs the cordial she pours for him in a gulp. The interview continues.

The room they are sitting in is luxuriously furnished. She moves closer and stares at him frankly. Does he think he can draw her face, and if so, what will he charge? He stammers out a price, which she ignores. Will he… will he keep her name and address a secret between the two of them, forever? When he agrees, she asks if he has ever drawn someone full figure, and then she cuts to the heart of the matter. Naked? she says.

∞

About midway through Les Miserables, Victor Hugo describes the moment when the crippled gardener Fauchelevant, Jean Valjean’s friend and accomplice, receives a piece of disastrous news, news that threatens to upset all the intricate plans the two men have made and to put both of them in mortal danger. The announcement is so shocking it almost knocks Fauchelevant off his feet. “If,” writes Hugo, “you somehow managed to survive a cannonball that hit you square in the chest, you’d probably look something like Fauchelevant at that moment.”

Shock, paralysis, cannonballs to the chest. Maybe this was just a thing with the war-weary French in the nineteenth century, the hyperbolic metaphor they used for expressing surprise. But according to Audubon, the word “naked,” as it fell from the lips of this beautiful woman, assumed the shape and force of a cannonball that tore through his heart and rendered him speechless.

His nervousness becomes so apparent that it affects his companion, who stands up and begins to pace back and forth across the room. Finally, she collects herself and sits beside him again. Then she tells him precisely what she wishes him to do.

“I want you to draw my Likeness and the whole of my form naked, but as I think you cannot work now, leave your Port Folio and return in one hour. Be silent.”

∞

Philip Roth’s late masterpiece of a novel, Sabbath’s Theater, deals with a bitter, sixty-something anti-hero named Mickey Sabbath, a man so sex obsessed and guilt ridden that, as his potency begins to fade, he can’t see any point in continuing to live.

In a remarkable passage deep in the novel, Sabbath rants—with obscene, alliterative gusto—against the popular preoccupation with the beauties of nature. It’s autumn, and he’s sitting in his car looking out the window at a New England hillside covered with trees whose leaves have turned different shades of yellow and red. Why do people gush over this “polychromatic perfection,” this “perennial profusion of pigmentation” that occurs so predictably year after year after year after year? Can these desiccated leaves really hold a candle to the whorehouses of Rio de Janiero that he visited as a teenager in the merchant marine? The mere memory of those places can still excite Sabbath, an old man in his sixties. He stipulates that he’s thinking of “the best places, the places where there were the most beautiful girls…. So many hot, beautiful women.”

How pale and lifeless his present seems compared with his past. “And he had sequestered himself in New England! Colorful leaves? Try Rio. They got the colors too, only instead of on trees, they’re on flesh.”

In one sense, this is just another reworking, although one grounded in the world weariness of Ecclesiastes, of the battle between flesh and spirit that plays out in every human soul. Autumn leaves have a beauty that we react to on a spiritual level and that appeals to our better nature. Hot sex with prostitutes satisfies one of our primal urges while degrading us to the level of the beasts.

But let’s be honest, says Sabbath. We are beasts, and anyone who denies us the right to quench our sexual thirst in any way we please is nothing but a self-righteous hypocrite. Society, for him, with all of its laws and taboos, is little more than a mendacious pact among puling hypocrites who say one thing and do another. The pathetic, middle-class reverence for the beauties of nature is only one of its more insincere manifestations.

∞

One reason Audubon cuts such a striking figure in American culture is that for him, and in spite of what appears to have been a pretty strong sex drive, there was little difference between a migrating warbler and a woman’s naked body. They both evoked in him a response so strong that it stirred to life his most powerful emotions and deepest thoughts. He found birds to be so beautiful that they excited physical responses that can only be described as sexual, and the most attractive women he met inevitably made him think of … birds. It’s not too much to say that for Audubon, the feather and the flesh were one and the same.

When he was courting his wife-to-be, a young neighbor named Lucy Bakewell, Audubon would take her to a cave on his Pennsylvania farm, and there the teenaged couple watched as a pair of Eastern Phoebes built their nest and copulated. The birds chirped as they caressed each other, just as the human couple sighed and exclaimed between their kisses. Writing about these scenes later in his journal, Audubon noted that the birds’ lovemaking, with all its preliminaries of song and touch, demonstrated not just the culmination of an instinctual act but the presence in these feathered creatures of genuine and specific emotions, emotions that they experienced in ways similar to their human counterparts:

“[their] remarkable and curious twittering…. While both sat on the edge of the nest at those meetings…. It was the soft, tender expression, I thought, of the pleasure they both appeared to anticipate of the future. Their mutual caresses, simple as they might have appeared to another, and the delicate manner used by the male to please his mate, riveted my eyes on these birds, and excited sensations I can never forget.”

Of course those sensations had something to do with his female companion at the time, and for the rest of his life, whenever Audubon laid eyes on an Eastern Phoebe, he would think of the pleasure he took in making love to his wife.

Audubon’s tendency to transform birds into women and women into birds was a central theme of the Canadian writer Katherine Govier’s fine novel Creation, which dealt with the aging artist’s time in Labrador. Govier speculated that Audubon’s late infatuation with the naturalist John Bachman’s sister-in-law, Maria Martin, was something of a valediction both to birds and to women: “She was his last young woman, his last rapture, and his last bird.” What did women and birds share in common that could so unite them in the mind of the artist? Govier thought the answer to be quite simple: Beauty. Audubon, she wrote, was “[beauty’s] captive. Powerless in its face, whether bird or woman.”

The ability of beauty to blur the lines between different species was particularly evident in the ten-day relationship that developed between Audubon and the Fair Incognito, and that he memorialized in a letter to—of all people—his wife. It was as if he were describing for her, as he had so often in the past, his discovery of another nondescript, the term Audubon used for a species of bird as yet unknown to science.

To be continued …