Quietly chanting crossword puzzle clues instead of the divine office, she sat behind the wooden desk at the front of the room and waited patiently, patiently for us to finish the final exam. Sister Mark Marie, a pencil in one hand and the Globe and Mail in the other, unruly locks of grey hair wisping out from beneath her wimple. She cultivated a disheveled look, complete with tea stains on her blue habit and bread crumbs clinging to the fabric. When her colorless lips parted, they revealed a set of bunched yellow teeth, and her eyes behind the wire-rimmed glasses always had a worried look, as if she’d just learned on good authority that disaster was imminent.

Seventeenth-century poetry and prose, a third-year course in the English department. Packrat me, I still have the questions from that exam, mimeographed in blue ink on a sheet of the cheapest paper, now gone yellow with age. “Write a short essay on the imagery or structure of Paradise Lost.” “Consider the religious or moral attitudes in the poetry of two of John Donne, Ben Jonson, Herbert, Crashaw, Marvell, or Herrick.”

According to rumor, she was a late vocation. According to rumor, she’d worked into her thirties as an executive secretary for a Bay Street lawyer who paid her handsomely enough that she could indulge a taste for the finer things in life.

She’d always been mad for anything to do with words. A scrabble champ and crossword whizz, and, more profoundly perhaps, a lover of English poetry, not just of the seventeenth century. If pressed—because you would have to press her to perform—she could recite whole scenes from Shakespeare, stanza after stanza from The Faerie Queen, and, according to rumor, she had Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake down pat and complete.

She corrected me once when I characterized Andrew Marvell’s famous line on “a green thought in a green shade” as a sensual image. She thought I should have used the word sensuous instead. To explain the distinction, she referred me to the Oxford English Dictionary, where I learned that: “While sensual is used to describe things that are gratifying to the body, and has sexual overtones, sensuous is used to mean ‘affecting or appealing to the senses’ in an aesthetic sense, without the pejorative implications of sensual.”

“In a way,” she wrote at the end of my paper, “isn’t that the whole point of “The Garden”?

When we have run our passion’s heat,

Love hither makes his best retreat.

Hasn’t the poet turned his back on the coarse gratifications of sexual passion (sensual) and retreated to his garden, where henceforth he’ll find pleasure in contemplating the beauties of Nature (sensuous) instead?”

When I re-read the poem with these words in mind, I could see her point, but the correction still rankled. I thought I could make a good case for sensual by citing Marvell’s explicit references to fond lovers and nymphs and to fruits such as grapes, peaches, and melons, that were clearly meant to evoke the sensation of a hand (or tongue) passing over a woman’s body. But I didn’t argue the point because I was reluctant to start a debate about sexual imagery with a nun. And yet the correction—the implication that I had made an error out of pure ignorance—that bothered me for some time to come.

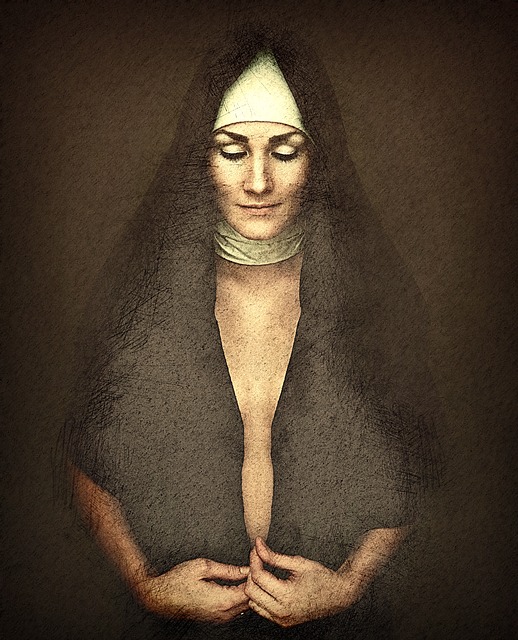

Now I wonder if this distinction between sensual and sensuous isn’t more a factor of age than perception. As we grow older and each of us assumes the trappings not so much of sexlessness but androgyny, does our preoccupation with sexual matters inevitably give way to something more refined? At the time he wrote “The Garden”, Marvell was in his thirties. Perhaps by then he’d passed from an obsession with all things sexual to a more general fascination with the natural world. Sister Mark Marie was in her thirties when she entered the convent. Had she, in her youth, felt the pressure of her sexual urges and waited till they’d grown less insistent before she embraced the religious life? Surely, by the time I knew her, when she was in her sixties, she was more in tune with the sensuous than the sensual side of life. If nothing else, we can assume that much, can’t we?

The first assignment she gave us that year was an essay of two thousand words on a topic I’ve forgotten. Two thousand words works out to about ten typewritten pages. In those days, of course, we all used typewriters for our written assignments. For Sister Mark Marie, I typed my essay on fine, one-hundred-percent cotton rag paper that I’d bought in a stationer’s shop on Bloor Street. Each sheet carried a watermark that you could trace with your fingertips, and the surface of the paper was slightly pebbled to the touch.

I used this quality of paper not so much to make a good impression but because working with it gave me pleasure. I liked the tactile feeling of the paper itself, and I liked the way it took the impression of the keys. They sank into the thick paper like a branding iron sinks into the skin of a calf.

I remember passing my paper to the front of the room on the day it was due. I remember the way Sister Mark Marie collected all the papers and then arranged them into a pile on top of her desk. She leafed through them with an abstracted look on her face, then her eyes focused, and she extracted my paper from the bundle. Running her hand over the title page, her lips parted and her body actually shivered with pleasure.

“I envy you boys and girls so much,” she said (we were all in our twenties). “You can afford to buy such good typing paper.”

She shuffled the papers all together again, tapped the bottom of the pile on the table, and then laid them flat. In a gesture of resignation, she patted the pile with the palm of her hand and said, “Ah, well.” Perhaps she succeeded in summing up her entire life with those two words, a life of deliberate self-denial and of unabashed appreciation for the things denied.

In the meantime, something odd had happened to me, sitting at the back of the room. Perhaps because the page she caressed came from me and I’d expended so much effort on writing the essay and presenting it in an attractive fashion, perhaps there was still something of me—some incorporeal remnant—clinging to the paper she touched. I don’t know how else to explain the sensation I experienced at that moment, the physical sensation of a finger tracing the line of fine hair that extends from the navel to the top of the pubic bush, of a hand passing over the pebbled skin of my groin, but it was so pronounced and unexpected that I can still feel it today if I make even half an effort. Sensual, I say and say it again. Sensual, not sensuous.