I. The photo

This all started at the end of September 2019, when a friend emailed me a photo she’d taken of a Black-legged Meadow Katydid. My friend and I are birders, and we share a subsidiary interest in butterflies and dragonflies. But katydids? I’d never seen one, so had never felt the urge to pursue and photograph them in the way I did those other creatures.

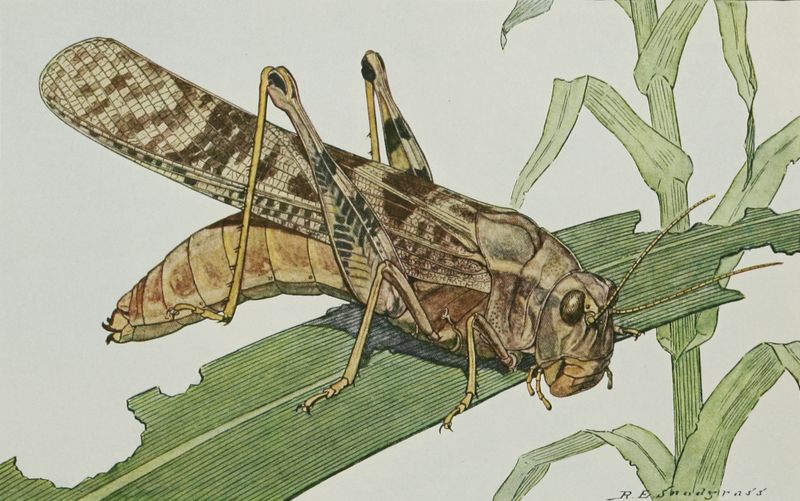

As soon as the photo appeared on my computer screen, I was fascinated. A katydid looks something like a grasshopper, but a grasshopper whose various body parts have all been struck by a magic wand.

Grasshoppers have thick, stubby antennae, but a katydid’s antennae are thin, gracefully held, and ridiculously long, in some cases twice the length of the insect’s body. The legs, especially the hindmost pair, are even bigger than on a grasshopper, and the eyes are like saucers, wide, staring, but with a glimmer of intelligence. The peculiar thing is that all of these outsized attributes are so well integrated that katydids are formidably efficient at feeding and protecting themselves (they are swift and prodigious jumpers) and at reproducing their kind.

Then there’s the matter of color. The katydid in my friend’s photo had legs of a black so rich it gleamed, and it gleamed so deeply that the legs appeared moist. The head was cardboard brown, and the wide eyes were the same shade of orange that you find on a ripe pumpkin.

But more than anything, it was the green of this katydid’s abdomen that fascinated me. The abdomen was thick, like the fuselage of a B-17, and the color more vivid, more alive, than the green of leaves. It was not just a living green; it reflected a higher consciousness than the vegetable, one that moved in reacting to threats and attractions, one that betrayed a type of thought that surpassed mere instinct.

The Catholic Church has assigned colors to each of the three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity. Green is the color of hope. The hope I conceived while looking at my friend’s photo was that I would find a Black-legged Meadow Katydid myself and take my own photo, and in this way begin to know something about this uncommonly beautiful insect. I told myself I’d start looking immediately, even though I didn’t know where or how to look. The truth is, I was on the verge of becoming obsessed by this bug, but then I blinked, and it was winter.

II. Research

Over the winter, I did what I always do when I want to learn about something: I read everything I could get my hands on. Two books in particular. The first was a field guide to the insect order Orthoptera: Capinera et al., Field Guide to Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets of the United States (Cornell University Press, 2004). This book has the virtue of being comprehensive and informative (the range maps also show which species appear in Canada), and it comes with excellent color illustrations. Its main fault is a dryness of style. In reading the text, I never felt the author lifted his hand and attempted to touch me.

The second book was much older, more discursive, and unashamedly enthusiastic: R. E. Snodgrass, Insects: Their Ways and Means of Living, Volume Five of the Smithsonian Scientific Series (Smithsonian Institution, 1930). Here’s how Snodgrass introduces his text on the Round-headed Katydids: “The members of this first group of the katydid family are characterized by having large wings and a smooth, round forehead. [They include] species that attain the acme of grace, elegance, and refinement to be found in the entire Orthopteran order.”

By reading these books, I increased my knowledge of katydids a hundredfold. For brevity’s sake, here’s a shortlist of things I learned that would assist my search for the Black-legged Meadow Katydid the following summer.

a. Diversity. The Black-legged Meadow Katydid is not the only species of its kind that inhabits my local area, which consists of Toronto and southern Ontario. About fifteen different species can be found here, including the Oblong-winged Katydid and the outlandishly named Sword-bearing Conehead.

b. Season. Katydids are, at least in their northern ranges, high-summer, late-season insects. In Toronto, I had no hope of seeing one until July at the earliest, and August and September would probably be the most productive months.

c. Habitat. A few katydids, including the Common True Katydid, live in the tops of tall deciduous trees—maples, oaks, cottonwoods, etc.—and rarely descend to the ground. However, most species inhabit meadows, abandoned farm fields, wildflower prairies, parks, and gardens.

d. Song. Almost all the katydids, like their cousins the crickets, are enthusiastic singers. Or, to put it more scientifically, they are skilled at stridulation. Katydids lack a voice box; the sound they produce comes from rubbing their forewings together. Each species has a distinct song, so having some familiarity with the songs (several online sites exist) can be a useful tool in finding and identifying the different types. Some katydids (again, like their cricket cousins) function as living thermometers, since the speed of their song increases during hot weather and slows down during cold. In fact, there’s a precise formula, which I won’t give here, for determining the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit by timing the speed of a katydid’s song and adding a certain figure to the number of chirps recorded.

I began to think of the katydid’s coloring as a kind of green mercury in which I could read at length about the subtle relationships between the insect and its environment.

III. The instrument

A few years ago, I was in a local park when I ran into someone I hadn’t seen in a while. He was leading a nature walk and had a dozen people in tow, but when he saw me, he stopped to talk. He asked if I was still birding.

“Not so much,” I said. “I’m more interested in bugs now, especially dragonflies.”

His eyes lit up. “Oh, I know exactly what you mean. But if you’re into dragonflies, then where’s your net?”

I held up my camera and said, “This is my net.”

Every pursuit has its own set of tools or instruments that aid in the endeavor, often by serving as extensions of our natural senses. In my pursuit of birds and bugs, the instrument I’ve come to rely on more than any other is a camera with a telephoto lens.

The camera I use is a Canon EOS 7D Mark II with a 100mm-400mm lens, also a Canon. This is standard gear for birders, but because of a close-focus feature on the lens, it also works well for insects of all kinds.

Aside from technical matters, what I like about my camera is that it’s an instrument in the best sense of the word, which is to say, in the Thoreauvian sense. As a skilled surveyor, Henry David Thoreau knew the value of instruments in any kind of scientific endeavor. One of his chosen instruments was a telescope, which he bought with some hesitation and at great expense, the better to see the birds that lived in the fields and forests surrounding his hometown of Concord, Massachusetts.

According to Thoreau, the very root of the word “instrument” indicates its higher purpose, which in every case is to increase the user’s knowledge. The English term has the same Latin root as “instruct”—struere, which means “to pile up;” instruere means “to teach,” specifically by piling up the student’s knowledge in an incremental way.

An instrument, then, is anything that assists in our education, and each time we use a particular instrument, we increase our fund of knowledge. Thoreau believed very strongly that we should all be lifelong learners, and that we learn, in large part, thanks to the instruments (including books) that we choose to help us.

Once the summer returned, I would employ my chosen instrument, the camera, to learn as much as possible about the Black-legged Meadow Katydid. What would I see thanks to this instrument, and, more importantly, what would I learn from what I saw?

IV. Preliminaries

Starting in April, I was in the field at least once a week and often more than that. I found my first katydid on August 9. It flew up to the top of a shrub beside the trail I was following in Taylor Creek Park. A male Fork-tailed Bush Katydid, its whole body a lovely shade of living green. This is one of the larger and more common katydids in North America.

I took several photos. One shows the katydid with its foot in its mouth. According to Snodgrass, this qualifies as a typical pose for the species.

The katydids are all very particular about keeping their feet clean, for it is quite essential to have their adhesive pads always in working order; but they are so continually stopping whatever they may be doing to lick one foot or another, like a dog scratching fleas, that it looks more like an ingrown habit with them than a necessary act of cleanliness.

I was so taken with this first sighting that I returned to the same spot exactly one week later. The moment I started walking the trail, I saw several katydids clinging to bushes that were still wet from a morning shower. In contrast to the Bush Katydid, these were quite small and not entirely green, but different shades of brown along the back. A Short-winged Meadow Katydid, another incredibly beautiful insect with its own complex structure. I took several photos of a female with her long, saber-like ovipositor.

After this, I felt I was on a roll. All I’d have to do would be to return to this park week after week, and eventually I’d find my target species, the Black-legged Meadow Katydid. But then … nothing.

For the rest of August and all through September, I didn’t see another katydid. The closest I got was a Black-horned Tree Cricket, a kissing cousin to the katydids, but whose green coloring seems pale in comparison. By the first week of October, I’d more or less given up the search and turned my attention to fall caterpillars. By then, it was so late in the katydid season that it seemed likely winter was about to frustrate my search again.

V. Discovery

At the end of September, I took a photo of an Asteroid Moth caterpillar, a completely different study in green, a green that melts into yellow, and this sealed the transfer of interest from katydid to caterpillar. Like many a desperate lover, I turned to what was available to supply the place of the one I desired.

On October 14, I was in Tommy Thompson Park on the Toronto waterfront, working through a stand of dried-out goldenrod where someone had seen a Smeared Dagger Moth caterpillar the day before. Suddenly, I spotted a familiar profile, the long, wispy antennae and the lanky, adolescent legs. I knew at once I had a katydid, but, unfortunately, the bug was backlit by the sun. Not only couldn’t I get a focused shot, but the glare was so intense I found it impossible to identify the katydid by species.

I started edging my way around to the other side of the bug to put the sun at my back. The goldenrod was so thick in this spot that many of the stalks were intertwined. Every time I took a step, the whole assemblage lifted and swayed. I was sure the katydid would fly off before I could set up, but in defiance of all precedent and expectation, it held in place until I reached a small clearing where I started taking photos again.

The katydid sat on top of a goldenrod plume. The flowers were all dried out; they’d turned white and gone to seed, but they formed a thick cushion where the bug could sit and eat and take stock of its surroundings.

Through the camera lens, I could see the katydid’s black legs and green abdomen. I’d finally found the object of my search, the thing I’d been hunting for—either in my mind or in the field—over the last twelve months. And a female at that, with her scimitar-shaped, mahogany-colored ovipositor.

As I watched the katydid through the lens, she was watching me. I could see her eye roll every time I moved to one side or another; I could see her legs re-arrange themselves in response to the slightest gesture I made. Was she getting ready to jump, or simply settling deeper into her cushion of flowers?

I admired not just the insect herself but this platform on which she chose to sit. What queen ever possessed a finer throne or one more suited to her form than the katydid and this desiccated seedhead of a goldenrod stalk? It was cushion, throne, dinner table, and observation deck all at once—everything she needed at the moment and for as long as the moment endured. Above all else, the flower plume formed a monstrance for displaying its perfect host to the wondering eye of the viewer.

If I were asked to summarize what I learned from my search and from the end of that search in this encounter, I’d say two things. First, that sometimes hope has to settle deeper than the conscious mind in order to be realized. It was only when I gave up looking for the katydid that I found it. If I’d persisted in looking, I might never have seen.

Second, that there’s a sacramental element to discovery and observation. The sight of something beautiful and long desired excites a kind of wonder that unites the observer with the object of his attention, no matter how different those two things might be. Thoreau wrote about such an experience in his Journal when he described finding a new (for him) species of fish in “the glaucous water” of Walden Pond.

But in my account of this bream, I cannot go a hair’s breadth beyond the mere statement that it exists—the miracle of its existence, my contemporary and neighbor, yet so different from me! I can only poise my thought there by its side and try to think like a bream for a moment.

—Journal IX, 358-9, November 30, 1858.

To try and think like a bream is to identify one’s self with a fish. For me with the katydid, there wasn’t much trying involved. As soon as I saw it, everything seemed effortless and fell into place. By taking the photo, I participated in a type of sacrament, in the same way one takes Communion. In observing the insect displayed on its seedhead, bathed in the light that illuminated every aspect of its perfect anatomy, I recognized myself in something different. It’s not too much to say, so I’ll say it again: I took the photo you see here with the same feeling of reverence that I’d experience in swallowing the Communion host. By doing so, I participated in the mystery that lies at the root of our being. Dear reader, you can too.

Love the pix and reading the research!

Marija

Your journey of discovery is an exciting story…like sleuthing! You have the patience and the focus to continue until you get what you’re looking for–bravo! I love the idea of maybe finding a katydid with its foot in its mouth. And they are so beautiful!