The old man—boy complex

How could something originate in its antithesis? Truth in error, for example. Or will to truth in will to deception? Or the unselfish act in self-interest? Or the pure radiant gaze of the sage in covetousness?

—Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

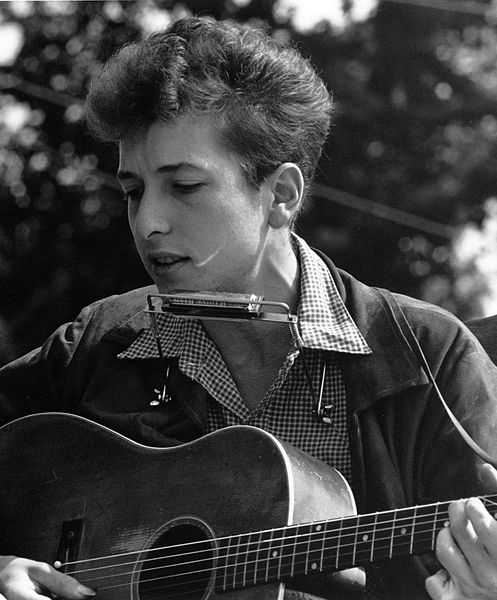

Or a grandfather’s voice in the body of a boy barely out of his teens? Right from the beginning, on the first album he recorded for Columbia, twenty-year-old Bob Dylan sang with the weathered and weary voice of an old man. Many of the things he sang about were an old man’s concerns, death being primary among them. Two of the songs on that album had death in the title, one referred to the singer’s grave, “Man of Constant Sorrow” mentioned death in the lyrics, and “Song to Woody” was dedicated to a man dying at the time in a New Jersey hospital. All through this debut album, Dylan’s voice had a husky, haunting, antique quality, and he sang with the authority of a tribal elder.

Many recording artists of the time—Harry Belafonte, Vic Damone, Tony Bennett—had smooth, trained voices that allowed them to hit all the notes and produce impressive vocal effects. Dylan only had one skill as a singer, but it somehow trumped all the rest: he knew how to sing a song. His first biographer, Anthony Scaduto, captured a moment that occurred not long after Dylan arrived in New York City from Minnesota. He was at a party, and a woman named Mikki Isaacson asked him to sing something. “He moved toward the group,” she remembered, “sat on the edge of one of the chairs, and began to play. He didn’t even have his own guitar with him, he borrowed someone else’s. And he sang a song about someone’s death, and I wept. I was just undone by it. He sang it almost as if he was throwing away his lines. He didn’t look at anybody, almost as if he was singing for himself, not for the rest of us…. He knocked everyone out.”

Forty years ago, I was working as a counsellor in a halfway house in Thunder Bay, Ontario. Most of our residents came from the provincial prison located just south of town on Highway 61. When my work was finished in the spring, I borrowed one of the house cars for a weekend and followed that highway across the border and down to Duluth, then took a series of backroads north to Hibbing. It was 1978. I’d been listening, closely, to Bob Dylan’s music for twelve years by then and wanted to see the town where he’d grown up. When he started recording in New York in the early 60s, Dylan seemed to have come out of nowhere. I wondered if there was anything that nowhere could tell me about the artist the young man became.

I wasn’t alone on this trip. Another counsellor at the house, a guy named Bill who was the same age as I, asked if he could come along. The secondary advantage to bringing Bill was that he could do half the driving. The main advantage was Bill’s personality. He was talkative and outgoing, whereas I tended to be shy and withdrawn. There was no doubt we would meet more people with Bill by my side, and I knew he’d do everything he could to persuade them to talk.

A brief selection of adjectives that writers have used to describe Dylan’s singing voice:

croaky, harsh, nasal, flaying, acrid, and grating.

A selection of similes and metaphors:

- “[His voice] made him sound like a man from a chain gang whose nose had been broken by a guard’s rifle butt.” Anthony Scaduto.

- “He is consciously trying to recapture the rude beauty of a Southern field hand musing in melody on his front porch.” Robert Shelton.

- “[He sounds] very much like a dog with his leg caught in barbed wire.” Mitch Jayne, of the folk group The Dillards.

This last comment took on a life of its own and mutated through constant repetition into a kind of shorthand, all-purpose description—a meme, if you will—of Dylan’s singing voice as “a prairie dog caught on a barbed wire fence.” That nobody who employed the phrase had a clear idea of what a prairie dog in pain sounded like had no effect on its popularity.

As the rain rattled heavy

On the bunk-house shingles,

And the sounds in the night,

They made my ears ring.

’Til the keys of the guards

Clicked the tune of the morning,

Inside the walls,

The walls of Red Wing.

—Bob Dylan, “The Walls of Red Wing”

Several residents in the halfway house where I worked had a first name that began with the letter “L”: Lyle, Lorne, Leonard, and Lester. Leonard was in his mid-40s and had been sentenced for murder. He was tall and lean with leathery skin, and he had a guttural voice and a deliberate manner of speaking. All his adult life, Leonard had worked for lumber companies like Abitibi, sometimes as a lumber jack, sometimes as a heavy-equipment operator.

He liked to play cards. Once he stayed up all night drinking rye and playing poker with a truck driver who also worked for Abitibi. By 4:00 a.m., Leonard had lost all his money. He lived in the house across the street from the driver and went home to think things over. After a while, it occurred to him that the driver must have been cheating. Leonard took a Remington bolt-action 30.06 out of his closet and sat by the front window, waiting. When the driver came out to get the morning paper, Leonard shot him through the heart.

Leonard had his own room in the halfway house, and when he was off on a job for Abitibi, no one but the cleaning lady went into that room or messed with his stuff. When he was at the house, he liked to sit at the kitchen table with a coffee and a pack of Export A’s. He was obsessed with a televangelist named Garner Ted Armstrong who had a show called The World Tomorrow.

“He’s actually a Jehovah’s Witness,” Leonard told me once. “Not many people know that, and it’s never mentioned on the show. But he is. A Jehovah’s Witness.”

“There’s a lot of them in Toronto,” I said. “They go around knocking on everybody’s door. Even get into the apartment buildings.”

“My sister’s a Jehovah’s Witness,” said Leonard. “That’s the one thing we don’t see eye-to-eye on. But she don’t do any canvassing.”

“Well, that’s good.”

“My mother was a Jehovah’s Witness too, sort of. She attended the prayer meetings and did some of the readings. But she didn’t try to convert anyone. And that’s the way my sister is. She attends the prayer meetings. But she don’t go door-to-door.”

Then Leonard changed the subject. “Listen, Ed,” he said. “Why in hell are you driving down to Hibbing, Minnesota?”

“That’s Bob Dylan’s hometown. Have you ever listened to his music?”

“No, I haven’t. And don’t intend to start now.”

“He wrote a song about a prison called “Walls of Red Wing.” It’s a place for young offenders just south of Duluth, right off Highway 61. Actually, it sounds much like the prison here in Thunder Bay, which is also on Highway 61. There’s a lot of weird connections like that in his music. The more you listen, the more your mind opens up to various possibilities.”

“Prisons,” said Leonard. He tapped with his lighter on the formica table top. “The worst prisons I’ve ever seen are those made of flesh and blood.” He tapped again with his lighter. “Those made of flesh and blood. And I happen to know what I’m talking about.”

Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell.

—Edgar Allan Poe, “The Tell-Tale Heart”

We left on a Saturday morning in the middle of April, when it was still so cold in Thunder Bay that we kept the cars plugged in behind the house. Driving through old Fort William in the dark, we crossed the river and the CNR tracks, then picked up Highway 61 by the airport and headed south from there.

The view out the car window changed as soon as we crossed the border. The one-horse towns with French names, the fish camps and marinas all seemed more populated and bustling than in Ontario, more brightly colored too, with flags and pennants flapping in the wind. Maybe this impression of liveliness was partly a factor of the spring, that we were travelling on what turned out to be a fine, sunny day, when the landscape seemed in the process of shaking off its winter’s sleep. All along the shore of Lake Superior, people were out in the streets and crowding the restaurant parking lots of the towns we passed. The water in the lake changed color as the day unfolded, from grey to green to the deepest blue.

We stopped for fried chicken in Grand Marais. Immediately, Bill started an argument with the girl behind the cash over the exchange rate she charged for our Canadian dollars. In revenge, he stuffed his pockets with wads of napkins from the holder on the table, he stuffed until the holder was empty. This scene would repeat itself, in one form or another, every time we stopped along our route. I soon realized that the downside to Bill’s extroverted personality was his tendency to pick fights with almost everyone we met.

The sun shone until just before we reached Duluth, around four o’clock in the afternoon. Then the sky clouded up and the air lost its buoyant quality. Duluth is a port city at the south-western-most point of Lake Superior. A harbor on the lakeshore has several long piers where freighters dock to take on loads of iron ore, timber, and grain. A towering lift bridge spans the entire harbor; from a distance, the metalwork tracery has the fine consistency of a spider’s web. Behind the port area, the land goes straight up, and most of the city is built on the side of a great hill. Whenever we stopped at a sign or a light, the car hung on the street at a forty-five-degree angle. On first sight, Duluth struck me as a grim and uncompromising place, a city of iron and rock and darkness.

Duluth is where Dylan was born as Robert Zimmerman in 1941, and where he lived until he was four. After the family moved to Hibbing, they would return to Duluth every year to visit, and Bobby would stay at his grandmother’s duplex. She was a transplanted Jew from Odessa. He remembered her as an old woman with a swarthy complexion. She only had one leg and would smoke a pipe while she rested in a chair and stared out the window of her place on Fifth Street. When he wrote about her in Chronicles, Dylan focused on the sounds he associated with the old lady, whose window overlooked Lake Superior, “ominous and foreboding, iron bulk freighters and barges off in the distance, the sound of fog horns to the right and left…. My grandmother’s voice possessed a haunting accent—face always set in a half-despairing expression. Life for her hadn’t been easy.” Those two sounds—of the fog horns and the woman’s voice, one mechanical, the other human—those sounds have a certain congruence or harmony. They ring together and form a chord in the reader’s mind, a chord that expresses the loneliness and hardship of one person’s life and the emotional bequest she made to her grandson, a legacy he never forgot. You might say she opened his ears to the suffering of others.

From Duluth, we took Highway 53 north, which brought us up to the town of Virginia on the Mesabi Range. The range is a geological formation where rich deposits of iron ore lie so close to the earth’s surface that they can be mined by digging open pits instead of underground tunnels. Over time, the pits take on a sprawling character and arrange themselves into concentric terraces. The deeper the pits go, the narrower they get, and the iron turns the exposed soil a dark red or chestnut color. The dimensions of the pit outside Hibbing are formidable: three miles long, two miles wide, and more than 500 feet deep.

From Virginia, we followed Highway 169 west to Chisolm and then turned south to Hibbing. The landscape was bleak and cheerless. Extensive tracts of spruce forest alternated with open, stony areas—alvars—where the vegetation consisted mostly of low-growing shrubs. The few towns we saw had a shut-up, depopulated look, and the occasional farmhouse on the side of the road looked lonely and decrepit.

We began to see billboards that referred to Hibbing. Some boasted that the town was the site of the largest open-pit iron ore mine in the world, others that it was the birthplace of Rudy Perpich, then governor of Minnesota. None of these roadside brags referred to Dylan, who by then had released more than a dozen albums that, taken together, had transformed the face of American music. The truth is, music, in any form, seemed a feathery, frail, and insubstantial thing set against the landscape that surrounded us. I reminded myself that the important consideration was not so much the impression Dylan had made on Hibbing as the mark Hibbing had left on him.

In March 1978, one month before Bill and I took our trip together, Playboy published a lengthy interview with Dylan. The journalist started by asking about his “visionary experiences.” What role, if any, did Hibbing play in the way those experiences developed?

In his reply, Dylan acknowledged the bleakness of the landscape where he grew up. In the winter, he said, everything was still for eight months, nothing moved. Then he reflected on what lay beneath the surface of that stillness. “The earth there is unusual, filled with ore. So there is something happening that is hard to define. There is a magnetic attraction there. Maybe thousands and thousands of years ago, some planet bumped into the land there. There is a great spiritual quality throughout the Midwest. Very subtle, very strong. And that is where I grew up.”

The question for me, as we approached this small and largely forgotten town on the Mesabi Range, was whether the “great spiritual quality” that Dylan identified as existing there would be in any way evident to us. Or would we, as short-term visitors to the place, remain on the surface of things, mesmerized by the banality of appearances?

You can find out a lot about a small town by hanging around its poolroom.

—Bob Dylan in a 1964 interview with Nat Hentoff for The New Yorker

Initially, we didn’t have any more luck finding references to Dylan in Hibbing itself than on our way there. The exit from Highway 169 was sharp and sudden. We missed it the first time and had to turn around in the parking lot of a Dairy Queen. We came into town on East Howard St. and followed it to First Ave. The intersection of First and 25thSt. forms the core of Hibbing’s downtown, and just north of this intersection sits Tuffy’s Bar. Bill parked the car in Tuffy’s lot, and we got out to survey the town on foot. It was the twilight hour; you could feel a cold wind blowing down the street from the north.

My first impression of Hibbing was of a place even smaller, more run-down and weather-beaten, than I’d expected. Next, I realized that all the young people on the street recognized us—instantly—as strangers and therefore as a source of amusement. Every time a car went by, the horn blared and the people inside hooted at us. Even two girls passing on their bikes jeered and shouted as they went by. This feeding frenzy lasted for about ten minutes, then the shouting died down, and everyone ignored us.

I went into a drugstore to buy cigarettes, and Bill cornered one of the clerks by the pharmacy counter. The two of them had a brief, intense exchange, then the phone rang at the back of the store, and the girl ran away to answer it. “No,” she called back over her shoulder, “they moved away years ago.”

Outside again, I asked if she’d been referring to the Zimmerman family.

“Yep. Gone with the wind.”

“Did she know anything else?”

“She didn’t know dip,” he said. “Not a fan.”

A sporting goods store dominated the corner of First Ave. and 25thSt. The store had big windows that displayed flannel shirts, work boots, and hip waders. One window was entirely given over to conibear traps and snowshoes, and it also contained a collection of stuffed animals: an otter, a lynx, a marten, and a beaver. The animals had been standing in place for so long that their coats had turned dusty, but their glass eyes, beady and unblinking, still glittered brightly. A yellowed card that rested against the beaver’s hind foot provided the taxidermist’s name and phone number.

We spent forty minutes walking up one street and down another. We passed the only theater in town, where Gene Wilder was playing in a film called “The World’s Greatest Lover.” We were the only people to be seen on most of the side streets that ran off First Ave. I thought of the lines Dylan wrote for “11 Outlined Epitaphs” and that appeared on the sleeve of his third album, The Times They Are a’Changin’:

the town I grew up in….

it was not a rich town

my parents were not rich

it was not a poor town

an’ my parents were not poor

it was a dyin’ town

(it was a dyin’ town)

The rhetoricians will tell you that repetition equals emphasis, and we felt the truth of Dylan’s redundant observation all around us in the empty storefronts and deserted streets. The temperature dropped as the sun set, and we were both getting cold and hungry. Just as I decided the whole trip had been a waste of time, we came up to a bowling alley. There was something inviting about its blinking neon façade, something warm and welcoming about the bright reds and yellows, and for the first time since we’d arrived in Hibbing, we saw people enter a building with a sense of purpose. Everyone who went inside carried the same type of small plastic bag; they were all bringing their own balls to bowl with. It was Saturday night, and the place was filling up fast.

I asked Bill if he felt like a game. Bowling was one of the few amusements we could share with the residents of the halfway house in Thunder Bay. Some of the guys were killers with a ball in their hand, and they’d forced both of us to raise the level of our game in self-defence.

Bill smiled, so I pulled the door open and we walked inside, following two men who went directly to the wooden counter at the back of the room. We watched the woman there take their money and give them both a pair of shoes. But when we approached and asked for a lane, she frowned and shook her head.

“It’s league bowling tonight,” she said. “This lane at the end is the only free lane, and those boys just took it. You can have it after them, if you want to wait.”

She looked at us with an alert expression, as if to say, You’ve got five seconds to decide. In her early fifties, she had high cheekbones and a bouffant hairdo, like a country singer.

“Okay,” I said. “We’ll take it.”

“You’ll wait?”

“Yes, of course.” We were strangers in a small town on Saturday night, and there was nothing else to do. I’d turned away towards the lunch counter, when I heard Bill say, “Are you busy right now?”

The woman snorted and asked why he needed to know. She was lightly built, and all her movements were quick and precise.

“Well,” said Bill, “if you’ve got the time, we’d like to talk with you about Hibbing for a while.”

I thought, My God, how crude and embarrassing.

“You see,” he continued, “we’re both from Thunder Bay, and we came down today just because we heard Bob Dylan grew up here. Did you know him? Could you tell us anything about him?”

At this and contrary to all expectations, the flinty, impatient expression on the woman’s face vanished. Her eyes softened and she grew excited.

“Oh sure, I knew Bobby,” she said. “One of my boys was the same age as him, and they used to run around together. This place right next door here? It used to be his daddy’s appliance store, and I was in and out of there all the time.”

I turned back to the counter, dumbfounded by our good luck. Bill said, “How long have you known him?”

The woman exhaled audibly, briefly.

“Since he was about this long.” She held her hands apart to show. He must have been a baby at the time.

We all moved around to the lunch counter. Bill sat down, and I lit a cigarette. The woman continued talking excitedly.

“Yeah, I’ve got lots of his poetry and every one of his records,” she said, smiling. She looked at me for a moment, then looked away and cocked her head wistfully. “His poetry’s really good, you know. There’s a lot of this in it.” When she said “this,” she tapped her temple a couple of times. Then she told us a little story.

To be continued …