The elderly boy topic

“Yeah, I’ve got lots of his poetry and every one of his records,” the woman said, smiling. She looked at me for a moment, then looked away and cocked her head wistfully. “His poetry’s really good, you know. There’s a lot of this in it.” When she said “this,” she tapped her temple a couple of times. Then she told us a little story.

“A lot of people around here look down on Bobby,” she said. “And they can’t figure out why everyone listens to his songs. One of my friends couldn’t stand him when he first got to be real popular. ‘He’s just a dumb kid,’ she’d say. Well, this same lady liked to read poetry, so one day I decided I’d try something. I took one of his poems—I have quite a few that he wrote out on paper and gave to me, but I didn’t use one of them. I took one that’d been published in a magazine and had his name at the bottom. Then I folded the page in a way that covered up his name, and I gave it to this lady to read.

“ ‘What do you think of that?’ I said. ‘What kind of a person do you think wrote that?’

“She read it over and asked if it was a young person who’d written it, and I said, ‘Yes, it was.’ Then she said that the person must have done a lot more thinking about life than was usual for someone of that age. So I unfolded the paper and said to her, ‘Look here, that person you like to call a dumb kid is the one who wrote this poem.’ ”

The woman nodded her head reflectively, enjoying the memory. Then she said, “He was here not too long ago.”

“Really!” we said together.

She smiled at our excitement. “Yeah, about six weeks ago he was in town.”

“What did he come for?” said Bill.

“See friends. He still keeps in touch, you know. Never broadcasts it when he comes to town; he likes to keep it quiet. He just visits with a few friends and then leaves again.”

Somebody wanting two Dr. Peppers, a Seven-Up, and a Coke called her away for a moment.

“So he was here just a little while ago,” said Bill, bouncing his fist off the countertop. When the woman returned, he asked if she could tell us where the Zimmerman house was located.

“Oh, I could give you directions,” she said. “But I couldn’t tell you the number or the street. Yeah, I’ve been there a hundred times, but you know how it is when you go to a place so often? You just go there, you don’t look at the street signs or anything. I think it’s over on 27th Street and 10th Avenue, which is east of here. I’m not really sure, though.”

Looking around, she saw the man in charge of the bowling alley. “Hey Dave,” she cried. “Where’s Abey Zimmerman’s old house?”

“Abey Zimmerman’s,” said Dave. He slapped the counter with a wet rag and looked at a man nursing a beer a few stools down from us. “Where is that, Jeff?”

“It’s over on 7th Avenue and 25th Street,” said the man without a moment’s hesitation.

“That’s right!” Dave nodded in agreement.

“Oh yeah—see?” the woman laughed. “I wasn’t even close.”

“Ask the cops,” chimed in a sullen guy at the end of the counter. “They were there often enough.”

After the hubbub died down, I asked the woman what Dylan was like as a boy. She thought for a moment, her chin jutted out and her lips in a grimace.

“Just like any other kid,” she began. “But he was … I guess the word I’d use is peppy, you know? He was always doing something. And you could tell by looking at him that he always had something on his mind. He was thinking.”

“Did he get in trouble much?” I was wondering about the reference to the cops.

“No, no.” She waved her hand as if shooing off a fly. “Not really. I wouldn’t say trouble, just the regular mischief that all kids get into.” She stopped. I thought maybe she’d taken offense at the question, thought I was getting a little too nosey. She bit her lower lip in a reflective way.

“I’m trying to think now if he drank a lot,” she said. “Some of the boys were big beer drinkers. But no, I don’t think he drank much at all. At least not back then.”

At this time, the one free lane opened up, and Bill and I had the chance to bowl. We bowled three games, and it was the first time either of us had played with an automatic scorer. When we brought our shoes and sheets back to the counter, the woman asked us what our plans were.

“Well, we’re just spending the night,” I said. “We drive back to Thunder Bay tomorrow.”

“Oh.” A disappointed look came into her eyes. It’s difficult now, forty years later, to describe that look with much precision, but it was like a thought tugged at her, and she was on the verge of saying something. She was on the verge, then the moment passed, and she restrained herself. The next day was a Sunday. Perhaps she was thinking of inviting us for dinner, perhaps she thought we’d enjoy seeing some of those handwritten poems Bobby Zimmerman had given her. But the moment passed, as moments do, and then we were gone.

In the opening chapter of Chronicles, Dylan writes about meeting the legendary producer and talent scout John Hammond, the man who signed him to his first recording contract. Of all the things Hammond said to him, one remark stuck in Dylan’s mind and resurfaced when he recalled the meeting forty years later. “I understand sincerity,” Hammond told him.

Sincerity is the word that occurs whenever I think of that woman in the bowling alley. She had a frank gaze. Her eyes looked directly at you, and when she spoke, you had the feeling she did so with perfect honesty, that she said exactly what she thought. Her attitude towards the boy who would become Bob Dylan consisted of pure affection. There was nothing small-minded, nothing suspicious or selfish about her feelings for him. And this came through so clearly, so strong, that it has affected the way I’ve thought of him ever since.

“She said he must have done a lot more thinking about life than was usual for a person of that age.” This observation corresponds pretty closely to different things Dylan has said about himself over the years. He told Anthony Scaduto he felt that he was more sensitive in some ways than his peers, and that this sensitivity made him something of a freak in their eyes. “I see things that other people don’t see,” he said. “I feel things that other people don’t feel. It’s terrible. They laugh. I felt like that my whole life.”

It wasn’t just a question of sensitivity, though, but of actual age, of feeling older—a lot older—than his biological age, that set Dylan apart. In Chronicles, he cites the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche to express this idea. “In Beyond Good and Evil Nietzsche talks about feeling old at the beginning of his life … I felt like that too.”

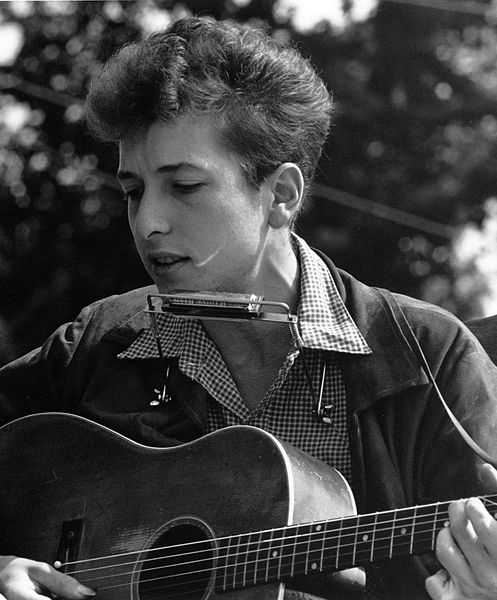

So, when he sang in that scratchy old man’s voice on the early acoustic albums, was Dylan just striking a pose, or was he trying to express the strange state of affairs that he perceived to exist within himself? Certainly more than a few of his fellow-folksingers thought there was something artificial, something disingenuous, about what he was doing. Ramblin’ Jack Elliot spoke for many when he told Scaduto: “He was trying to sound like an old man who bummed around eighty-five years on a freight train, and you could see this kid didn’t even have fuzz on his face yet.”

On the other hand, we have Dylan’s own repeated testimony to the effect that he felt the presence of an “other,” of someone different, within himself. When his girlfriend Suze Rotolo introduced him to the poetry of the French Symbolists, Dylan was particularly excited to discover Arthur Rimbaud, the poete maudit who testified to his own feelings of inner alienation. “I came across one of his letters,” Dylan says in Chronicles, “called ‘Je est un autre,’ which translates into ‘I is someone else.’ When I read those words, the bells went off. It made perfect sense. I wished someone would have mentioned that to me earlier.”

In singing with an old man’s voice when he was only twenty years old, is it possible that Dylan was doing something more than putting on a mask, adopting a pose? Instead, could he have been dealing with an unconscious state of affairs, one that resisted any kind of neat verbal summary and could only be expressed through performance, by singing simultaneously with the voice of an old man and the energy of a boy?

To answer this question, it might be helpful to consider what the medievalist E. R. Curtius identified as the puer senex or “elderly boy” topic. I had to read Curtius’ European Literature in the Latin Middle Ages as part of my course work in graduate school. Chapter 5 deals with rhetorical topics, which are figures of speech or commonly accepted ways of treating certain subjects. For example, the humility topic. As an aspiring poet, you would throw this in at the beginning of a poem. You’d start out by saying you were nervous, you feared that the story you were about to tell might be beyond your powers. You’d ask for everyone’s patience and understanding. In this way, you’d win the sympathy of your readers and encourage them to keep reading to the end.

If you wanted to praise someone—a king or a queen, a saint or a fellow-poet—you had other topics at your disposal. One was called the puer senex or “elderly boy.” Even as a child, you would say, this person had the wisdom of an old man. Curtius says this topic became such a commonplace in the Middle Ages that it outgrew its function as a rhetorical device and turned into something of an archetype, a projection of the unconscious mind. The image of the elderly boy is at once so strange and familiar, so packed with meaning, that it must be rooted in “the deeper strata of the soul” and correspond in some mysterious fashion to “the language of dreams.” In other words, the elderly boy isn’t just a kid who is smarter or more sensitive than the rest, but one who contains within himself two distinct identities—one old, one young—and who not only switches back and forth between the two, but who can be both at the same time, two at once.

“In dreams,” says Curtius, “it can befall that beings of a higher order come to us to encourage, to teach, or to threaten. In dreams, such figures can be at once small and large, young and old; they can also simultaneously possess two identities, can simultaneously be known and wholly unknown, so that—in our dream—we understand: This person is really someone else.”

But to what purpose? What does it mean for an artist to unite and harmonize within himself the two opposite identities of youth and old age? Curtius thought that the puer senex symbolized a “regeneration wish of the personality.” In this sense, it is an urge that, when realized, unleashes a remarkable vitality. It’s worth noting that even though the artifice involved in Dylan’s singing voice was obvious to other performers, his shapeshifting soon became convincing enough that it vanquished everyone’s objections. Even Jack Elliot succumbed in the end. “There was not another son-of-a-bitch in the country,” he told Scaduto, “who could sing until Bob Dylan came along.”

To be continued …