In its root sense, the French word derive is a nautical term that comes from the Latin rivus or river. It means “drift,” as a canoe drifts down the river or a ship drifts out on the ocean. In the second half of the 20th century, certain French writers appropriated the term as the name of a new method—a strategy—for exploring the city on foot.

According to the social critic Guy Debord (1931-1994), the most rewarding walks start without a preconceived route or destination. Instead, you should simply drift through the urban landscape by taking “the path of least resistance that is automatically followed in aimless strolls.” The point is to keep your eyes open and note the way the different neighborhoods or quartiers produce varied and specific psychological effects in you, the walker, as you execute your derive or drift. Only in this way, will you truly get to know the city; only in this way, will you succeed in penetrating at least part of its mystery.

Toronto

I suppose I’m intrigued by the practical applications of the derive because whenever I’ve been oppressed or overwhelmed by the difficulties of life, I’ve sought relief through taking long walks. For example, at a certain point in my life, I found myself in a kind of in-between-land, situated between the disciplined and highly scheduled time I spent at university and the responsibilities associated with married life and a career. It’s not too much to say that during this period, which lasted for about two years, my whole life was adrift. I had no sense of purpose, either in the short or the long term, and this was mirrored in the walks I took.

I lived in Toronto, that grayest of urbs, and these walks through different neighborhoods would last sometimes for hours. They had no stated starting point and no clear terminus; their only purpose was distraction. I was drawn to the poor parts of the city and to the people who inhabited them. It was as if I saw myself in these people. I could see in the bums and derelicts and streetwalkers, in the ground-down working poor, not just what I was at present, but what I would become—they embodied my future in all its hopelessness and fear.

I had no money to speak of, and there were times when, after paying rent, I couldn’t afford to eat. I’d walk down Spadina Avenue, through the red-and-yellow neon jungle of Chinatown, and look in the windows of the restaurants, at the people and at the plates of food in front of them.

Once I stopped before a restaurant on the west side of the street. The blinds were halfway down; all I could see was the table by the window, and only half of that. The group had just left, and the plate closest to the window was still full of food, of fried rice and uneaten chicken wings. The wings were plump and golden brown and streaked black with sauce. Not to be melodramatic, but I hadn’t eaten anything in two days, and while I stared at the plate of food that was about to be scraped into a garbage can, I thought of the line from Luke’s narrative of the Prodigal Son: “He would fain have filled his belly with the husks that the swine did eat: and no man gave to him.”

This was many years ago, and at the time, I didn’t know anything about the theory of the derive, of walking through a city not with a sense of purpose or destination, but merely with your eyes open, to note what might present itself and the way that presentation might affect your mood, your interior architecture. That each street, each block, each building façade or square of pavement, each person you passed, might have a specific and palpable effect on your psychological state, on the way you looked at your environment and on your own state of being within that environment.

It was only many years later that I read the novels of Patrick Modiano or the essays of Guy Debord, where the theory (Debord) and practice (Modiano) of the derive are treated. Back then, the only literary models I could look to for advice on walking were two Americans, Thomas Wolfe and Henry David Thoreau.

Thomas Wolfe

Thomas Wolfe’s work “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn” is one of those short stories that haunts the mind for years after you read it, creating its own space in the memory, its own reference point and hierarchy of meaning. Written in the Brooklyn slang of the early 20th century, the story tells of the narrator’s meeting with a strange young man who explores the different neighborhoods of Brooklyn by night. He has a map to guide him, but he also asks for directions from the locals, who can’t understand the purpose of his endless walks, can’t understand what he’s seeking to find in his nocturnal rambles.

As the narrator and this young man talk on the subway, they each stake out their own territory: the narrator, in spite of being a tough guy, is the typical petit bourgeois, the normal one, the regular Joe; and the young man represents everything morbid and dark and strange and threatening in life. The narrator tells him he’s involved with a hopeless task because “You ain’t neveh gonna get to know Brooklyn. Not in a hunderd yeahs.”—his aimless walks and all the maps in the world won’t be of any use in the end.

In turn, the young man asks how big Brooklyn is and why the narrator thinks he should avoid neighborhoods like Red Hook. Why?—he repeats the question three times. When the narrator replies evasively, the young man changes the subject completely. He asks whether the narrator knows how to swim. Oh, and while we’re at it, has he ever seen anyone drown? This is all too much for Mr. Down-to-Earth. He gets off at the next stop and the story comes to a sudden end there in the darkness of the underground. But by then Wolfe has accomplished something significant with this masterpiece of small proportions—he has established the link between walking and death, between exploring the city on foot and encountering one’s own mortality.

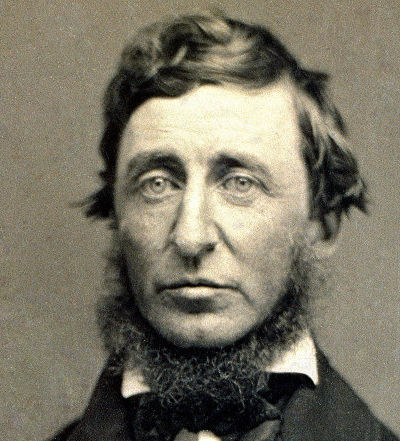

Henry David Thoreau

All his life, Thoreau was a dedicated, even a fanatical walker. He felt the need to walk, and walk far, every day of his life. In the essay entitled “Walking,” he says, “I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements.”

He uses the word sauntering advisedly; he thinks the term is “beautifully derived” from the French Sainte-Terre or Holy Land. For Thoreau, the verb to saunter not only carries connotations of slowness and aimlessness, but it is also rooted in the idea of finding a promised land, a sacred place. For him, making such a discovery is the end of all walking. He believed that every walk is a kind of pilgrimage or crusade, which, in its most perfect form, will result in a spiritual transformation.

In this sense, the practice of taking long walks has little to do with achieving cardio-vascular fitness. If you’re walking merely to promote your physical well-being, then you’re missing the point. “If you would get exercise,” says Thoreau, “go in search of the springs of life.”

For Thoreau, walking was a form of meditation, or what some people today call mindfulness. We must all “walk like the camel,” he declares, “which is said to be the only beast which ruminates when walking.” What shall we ruminate on? We must first empty our minds of all their worries, of all those “worldly engagements.” Then we have to focus completely on what we see in the present moment, to the exclusion of everything else. “Above all, we cannot afford not to live in the present. He is blessed over all mortals who loses no moment of the passing life in remembering the past.” Thoreau’s walks inevitably took him into the woods. To appreciate his immediate surroundings, he had to clear his mind of other places and of the people who inhabited them. “What business have I in the woods,” he wondered, “if I am thinking of something out of the woods?”

In his use of terms such as Holy Land and blessed, Thoreau was consciously employing a Christian vocabulary to link the practice of walking to a certain type of spiritual development. This is even more evident when he speaks of the total commitment that a truly dedicated walker must make to “this noble art.” He paraphrases the Gospel reference to the need for abandoning one’s family if one wishes to discover the Kingdom of God. “If,” says Thoreau, “you are ready to leave father and mother, and brother and sister, and wife and child and friends, and never see them again… then you are ready for a walk.”

The Christian references that are sprinkled throughout the essay come to a head at the end in a wonderfully detailed image of light. Thoreau was an experienced public speaker at forums such as the Concord Lyceum, and his essays—see particularly the thundering works he wrote in support of the abolitionist John Brown—often took the form of speeches that followed many of the rules of classical rhetoric. “Walking,” for instance, ends with a peroration or summing up that starts off with what appears to be a casual reference to the weather: “We had a remarkable sunset one day last November.” What made it remarkable was the cast of light as the sun peeped through a bank of clouds just before it disappeared. The passage is so finely developed that it’s worth quoting at length. Note the way Thoreau uses superlatives to convey the otherworldliness, the supernatural quality of the light he saw.

“I was walking in a meadow, the source of a small brook, when the sun at last, just before setting, after a cold, gray day, reached a clear stratum in the horizon, and the softest, brightest morning sunlight fell on the dry grass and on the stems of the trees in the opposite horizon and on the leaves of the shrub oaks on the hillside, while our shadows stretched low over the meadow eastward, as if we were the only motes in its beams. It was such a light as we could not have imagined a moment before, and the air also was so warm and serene that nothing was wanting to make a paradise of that meadow.”

It’s also important to note the way Thoreau links this one afternoon in autumn—one single day out of his whole life—to the concept of eternity. He does this by observing that the same phenomenon will happen “forever and ever, an infinite number of evenings.” The light is what makes him think of eternity and of the paradise that endures forever. “We walked in so pure and bright a light… so softly and serenely bright, I thought I had never bathed in such a golden flood, without a ripple or a murmur to it. The west side of every wood and rising ground gleamed like the boundary of Elysium.”

This is the point of all walking, he is saying, to awaken us to the presence of the sacred in the world where we live. “So we saunter towards the Holy Land, till one day the sun shall shine more brightly than ever he has done, shall perchance shine into our minds and hearts, and light up our whole lives with a great awakening light, as warm and serene and golden as on a bankside in autumn.”

A Comparison

The differences between Thomas Wolfe’s approach to walking and that of Thoreau may be obvious, but let’s summarize them here anyway. Wolfe focuses on “the dead,” Thoreau on “the springs of life.” Wolfe’s hero walks at night and in the city, while Thoreau walks by day and in the country. Wolfe’s character visits bars and slums; Thoreau walks through meadows and forests. Wolfe’s story is narrated in a kind of subliterate slang, while Thoreau writes his essay in formal prose and organizes his argument according to the rules of Ciceronian rhetoric. The meeting between Wolfe’s narrator and his hero takes place in the underground burrow of the subway, while Thoreau’s adventures are all decidedly above ground, en plein air. Wolfe’s story ends in mystery and darkness, Thoreau’s essay in a brilliant, other-worldly light that he thinks reveals the truth at the core of human existence.

But in a single matter they agree: That the serious walker is involved in an enterprise whose fascination is inexhaustible if only because one’s surroundings offer challenges that can never be fully mastered over the span of one person’s life. This idea is expressed in the title of Wolfe’s story and in a typically densely packed passage from Thoreau’s essay: “There is in fact a sort of harmony discoverable between the capabilities of the landscape within a circle of ten miles radius, or the limits of an afternoon walk, and the threescore years and ten of human life. It will never become quite familiar to you.”

You can rest assured, these two disparate authors believed, that whether in the city or the country, every time you set out on a walk, you will find something new and unexpected. Some different facet of the great mystery will be there—right out in the open—for anyone with the eyes to see.

But the question remains: Can these two divergent approaches to the art of walking ever be reconciled? Is it possible to transpose Thoreau’s fundamentally rural and ecstatic exercise into an urban context? In some important ways, this is what the French theory of the derive attempts to do.

To be continued …